Quaerere Verum

Contents:

I. Our current predicament

II. Universities in England and PHE: Big Business and National Politics in Local Areas

III. Operational Failures – HOW?

IV. What happened at the start of term? – A somewhat hypothetical retrospective

V. Underpinning Rationales – WHY?

VI. Concluding Remarks – A Second National Lockdown. What now?

I. Our current predicament

On the 13th of October, the leader of the Opposition, Keir Starmer, called on the government and the PM to follow the scientific advice of SAGE from the 21st of September 2020 and impose a national “circuit breaker” lockdown of at least two weeks. The next day, from opposite public-health perspectives, both Paul Goodman of the Conservative Home and Anthony Costello of the Independent SAGE critiqued Starmer’s announcement in ways that almost involuntarily converge to depict England’s current predicament: How can a country fight Coronavirus without a viable system of testing, tracing and isolating the virus, and without lockdowns?

To be concise, both Goodman and Costello started their critiques with the same question: how could a “circuit breaker” alone resolve the problem, unless the testing, tracing and isolation system was also massively and urgently reformed?

For Goodman, the test and trace scheme is lacking so much in capacity that it could never be reformed quickly, meaning the “circuit breaker would have to be switched on for the duration” effectively becoming “a full national lockdown of uncertain length” that would damage the economy even more and not stop the virus – a solution he finds entirely unacceptable. According to Goodman, Starmer knows this very fact but has sensed that the government has lost control of the Coronavirus and is only asking for a “circuit breaker” now in order to expose the PM and build on polling support for lockdowns. It is important to note here, that even for Goodman, the “circuit breaker” has an air of inevitability to it.

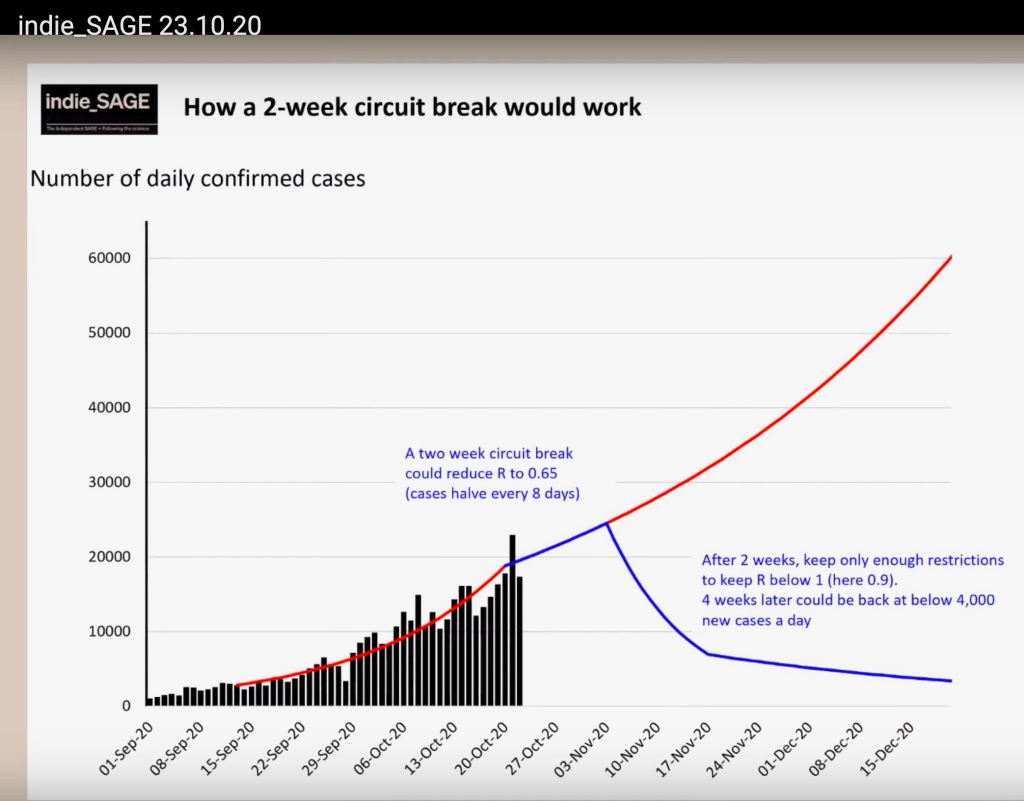

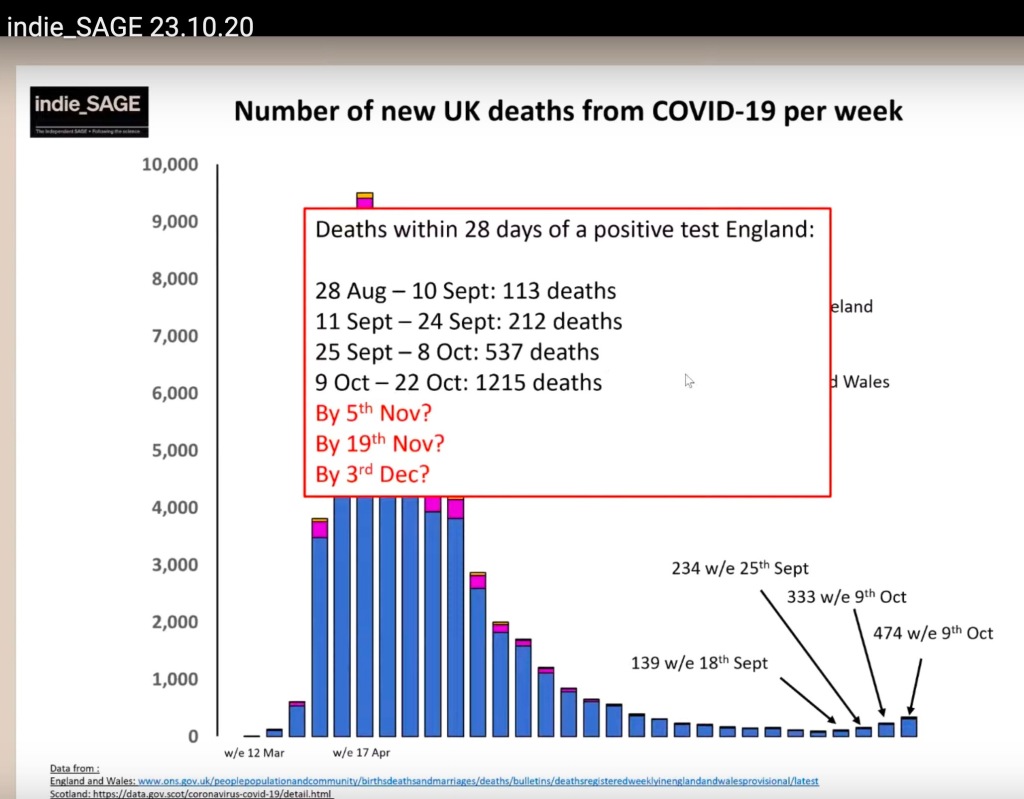

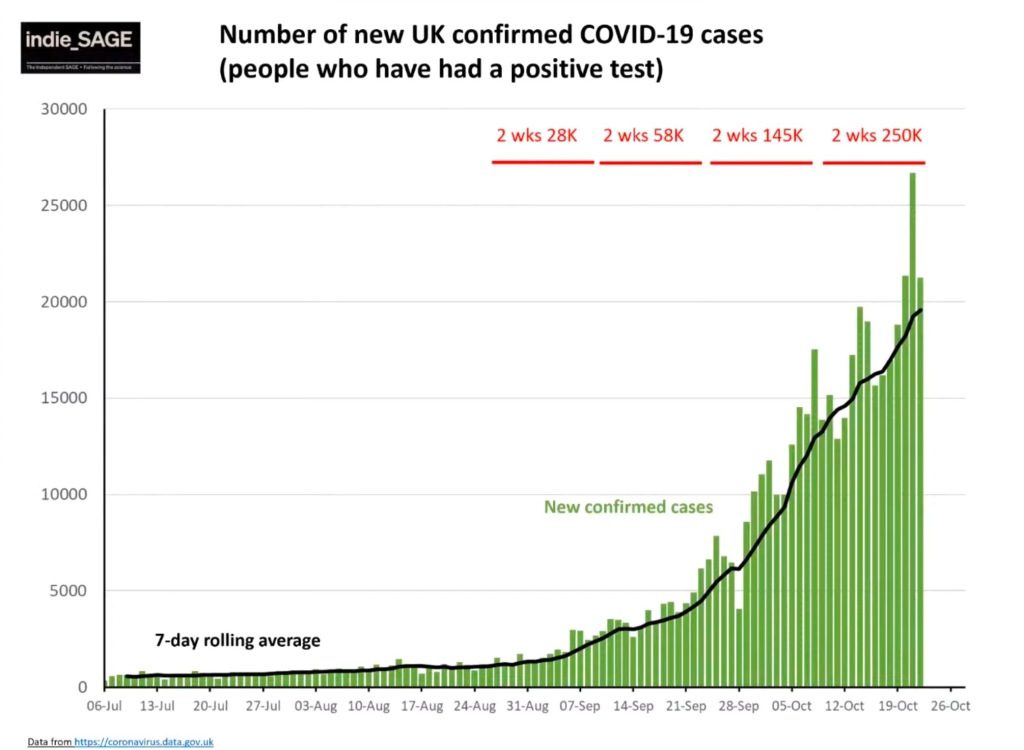

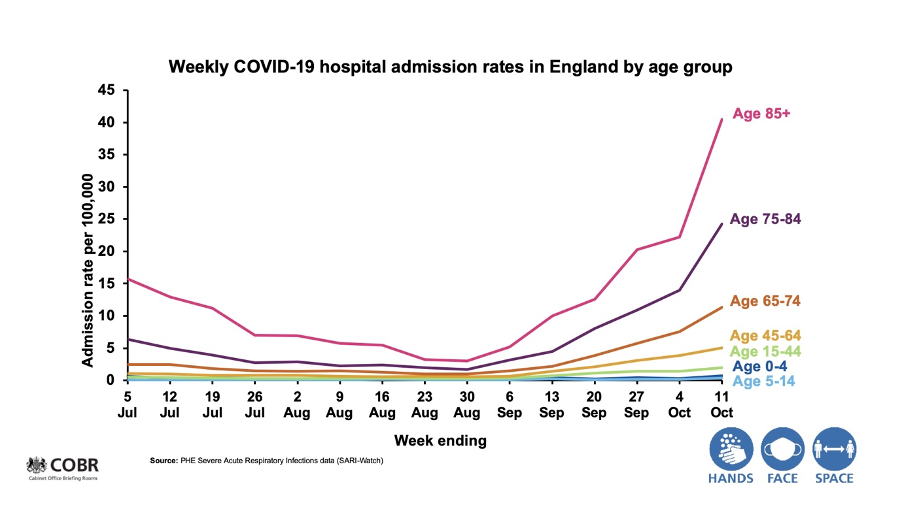

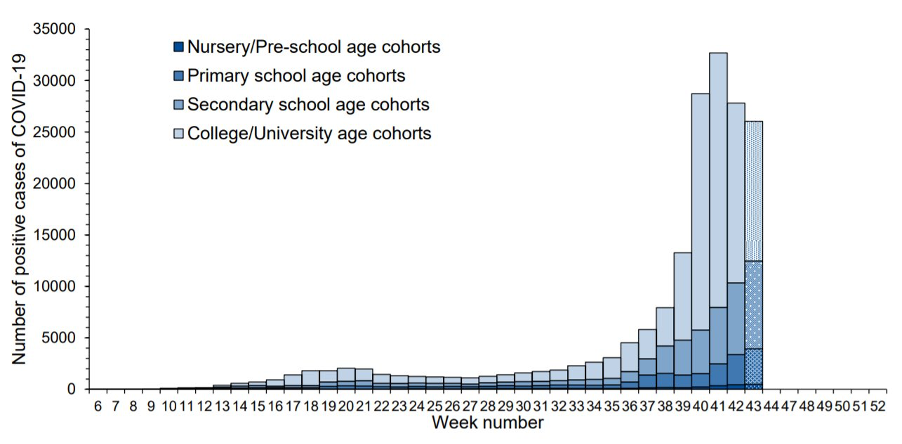

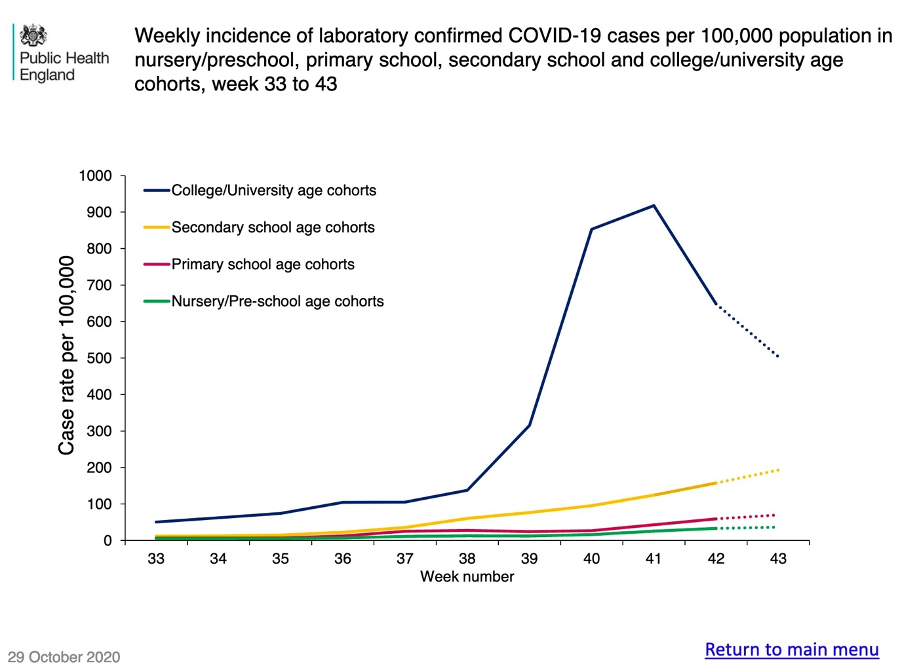

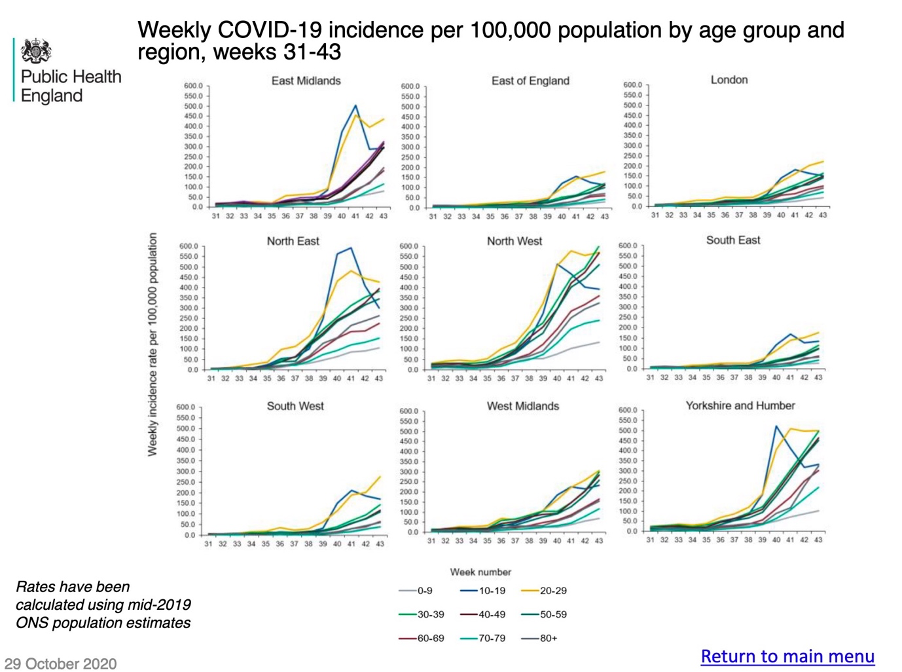

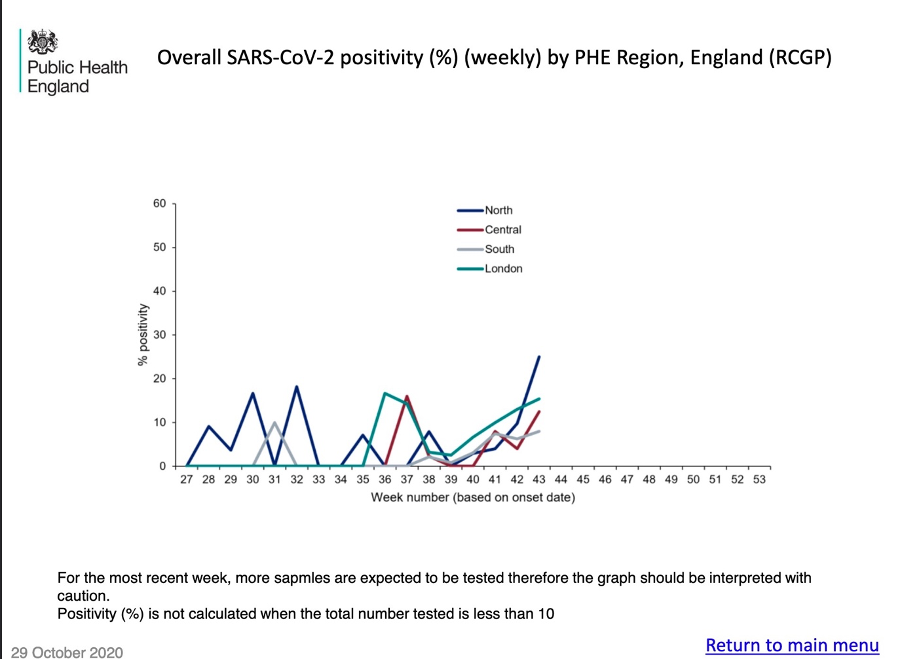

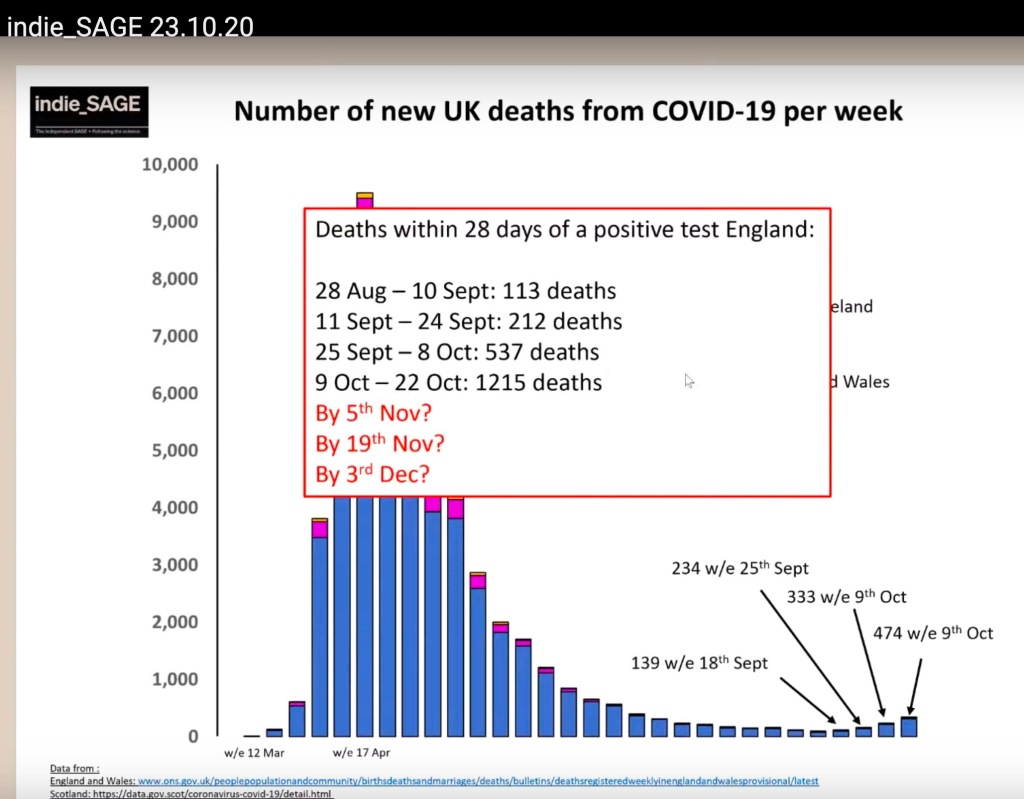

This is so, because, although he does not mention it, he must know, that like in the first wave, the current exponential growth in cases, and then in deaths, will soon be at a critical level once again. In other words, that Starmer is not just sensing that the PM has lost control of Coronavirus, but that he is scientifically assured that this has happened. That the same governmental delay that cost us so many lives during the first wave is occurring again, but amidst a second wave of the government’s own making. Looking at these two next charts, it is so easy to see why SAGE had requested a circuit-breaker on the 21st of September (a day and week of great importance in the opening of the Universities), why Starmer has requested one on the 13th of October, and why the Independent SAGE has asked for one on the 23rd of October:

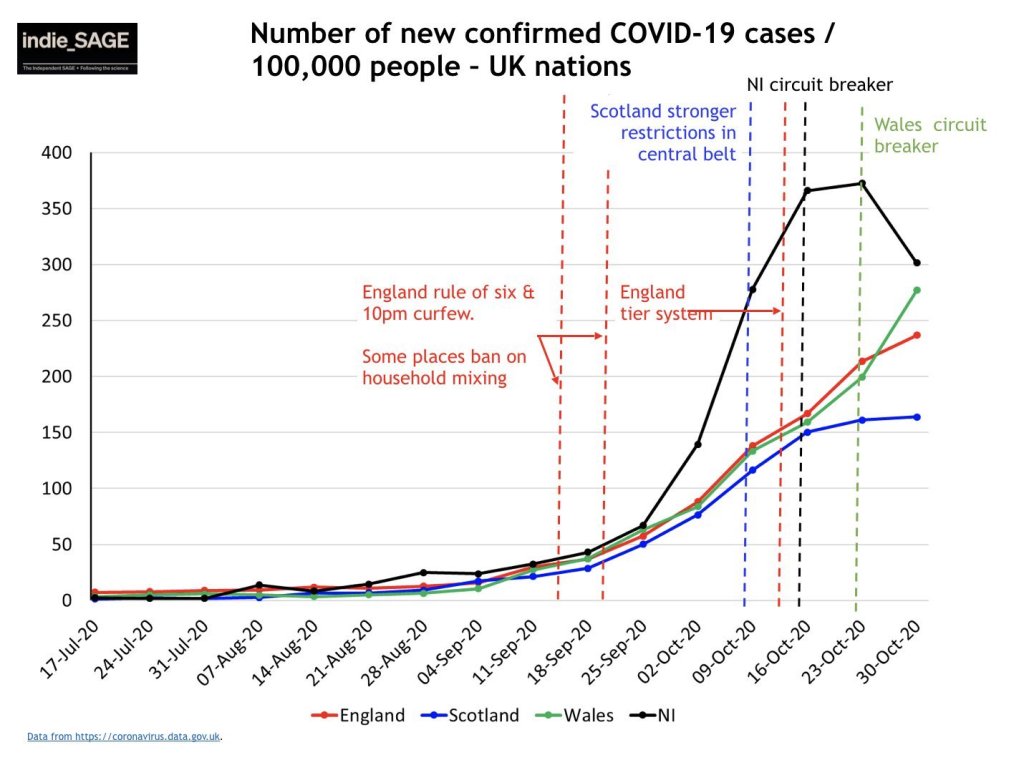

The important thing to also understand about these two charts is that the argument of both SAGE and the Independent SAGE is that the Three-Tier system of the PM (active from the 15th of October) will decrease somewhat the numbers but not do enough to arrest their exponential growth. We could thus argue that the PM and the Conservative government and party have opted to go against the government’s scientific advice, while the Welsh (circuit-breaker from the 23rd of October), Northern Irish (national circuit-breaker but with less restrictions than Wales, from the 16th of October) and Scottish (a Five-Tier system where Level 4 is similar to a full lockdown, to be implemented from the 2nd of November; but after having already introduced temporary restrictions on the 8th of October) governments have generally gone with it, although with variations. This means that possibly by the end of November and, quite surely by the end of December, we will likely have plenty of hard data regarding the effects of the four different systems, and of how important, or not, it would have been to follow the advice from SAGE and the Independent SAGE at the right time.

It can already be seen from a chart released by SAGE on the 30th of October that the English tier system has not had the effect the government has hoped for over more than two weeks, while NI and Scotland have done much better already, with the effects for Wales yet to show during or after next week.

(Source: here)

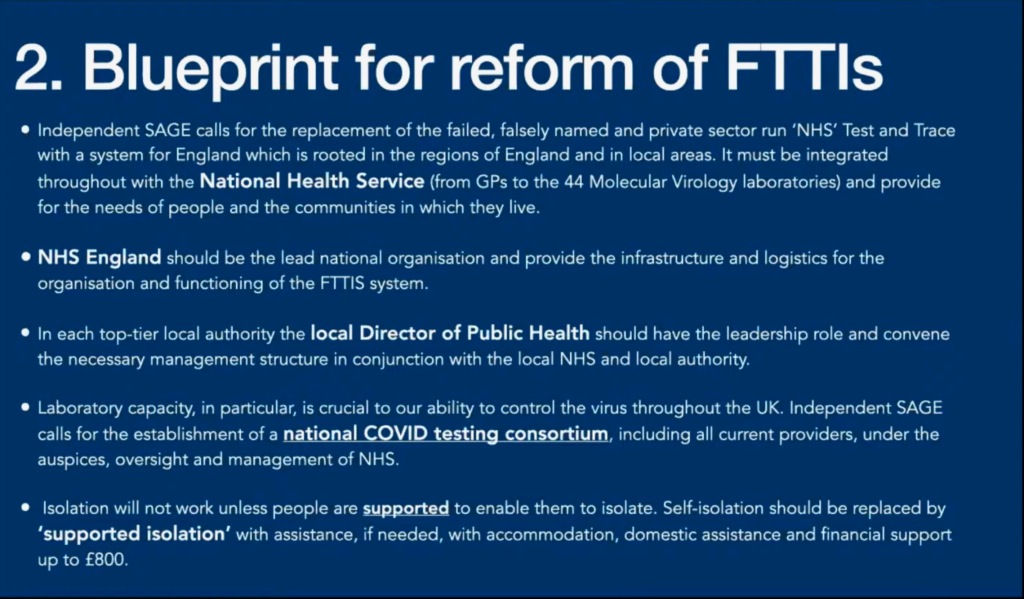

These charts also explain Costello’s argument. “A national lockdown is a last resort and an admission of failure”, he admits. However, in his view, “delaying restrictions would allow the virus to spread and cause greater economic damage in the long term” as well as loss of lives. Costello then decries the failed opportunity to build a viable test and trace scheme in the time afforded by the previous national lockdown and suggests measures that could be taken now – 23/10/2020:

The problem, which he does not address, is that while an extended “circuit breaker” could lower transmission of the virus for about two to three months, it is not at all clear that the existing test, trace and isolate system could be reformed in such a short period of time. If a viable testing, tracing and isolating system implies a move away from centralization to decentralization, from privatization to being a central part of the public health system, and from massive investment in private companies to massive investment in GP practices and the NHS (options to which this government seems most categorically opposed) then it is highly unlikely that such reforms could be undertaken in less than six to eight months. While Sir David King from the Independent SAGE argues that the test and trace system could be reformed to fully operate locally in a record time of about 4 to 6 weeks, a more pragmatic view would suggest that the government would need a similar amount of time just to find an agreement about how to reform the existing system. And this is all before the phases of planning and implementation when we must factor in the complex and time-consuming administrative overhaul effectively equivalent with the reorganization of both the NHS and of Public Health England, and of their current leadership.

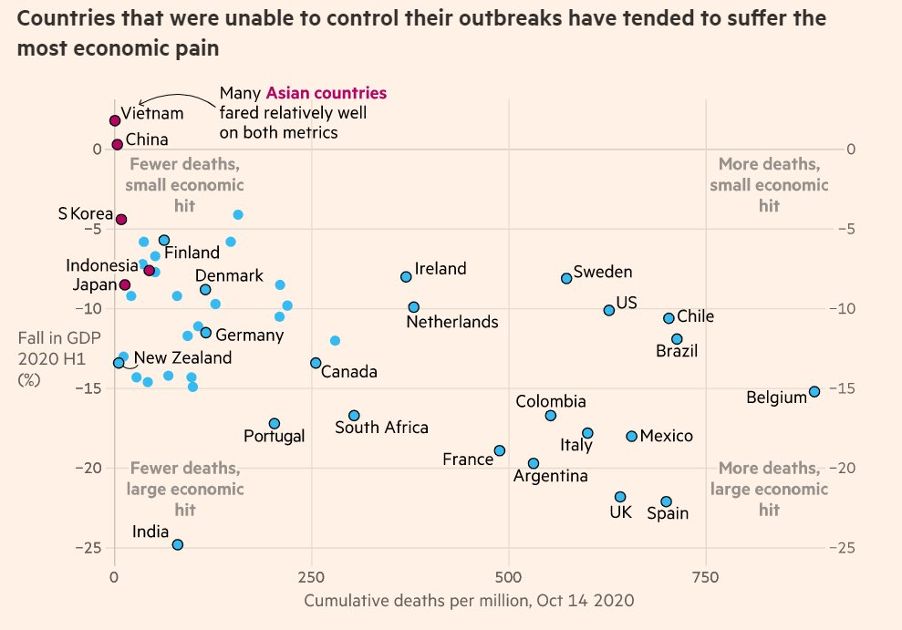

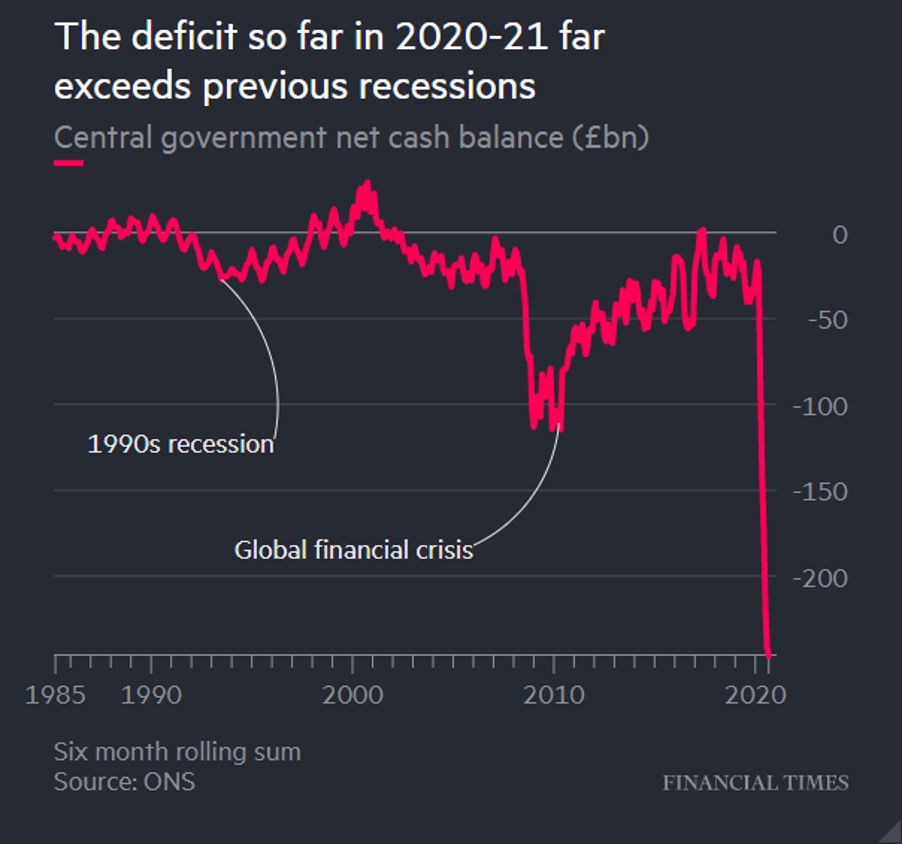

A more interesting proposal (but in my opinion, we are still grasping in the unknown for what could work for the UK in the medium to long-term) is that of “a coordinated circuit breaker followed by intermittent and contingent ‘reset’ periods” that “could avoid a longer lockdown, help the economy, keep a handle on COVID, and save lives.” However, this would require a commonly shared understanding of the virus that transcends ideological and political divides, and an unparalleled unity of vision and trust between local populations, scientists and the different levels of government, coupled with absolute and verifiable transparency concerning daily data about the virus. Movement towards such a shared vision cannot happen without the realization that the lockdown vs. economic growth opposition is likely a false dichotomy, inasmuch as those countries which managed to control the virus, managed to protect both a considerable number of lives and their own economies, while those that did not, usually suffered the most economic pain and the greatest loss of life (according to the FT):

It would seem then, that England is caught in a catch-22 scenario that could wreck the economy (either allow virus transmission to move towards exponential growth, which would severely impact the economy, or intervene through economically devastating national and local lockdowns), being punished for having failed to build its test and trace system during the first period of national lockdown.

Nevertheless, while the urgent reform of the testing, tracing and isolating system is clearly essential to any type of solution to the pandemic, and the more pragmatic hope here would be that a mix of public-private solutions could deliver the needed capacity in less than two or three months, neither the test and trace scheme, nor the tool of lockdowns, can, alone or together, contain the coronavirus crisis. The answer can never be just a technical solution like massive testing (or a vaccine, or anything else for that matter), something Paul Goodman fails to realize in his somewhat utopian espousal of the government’s proposed “moonshot”.

None of these instruments can function if our social and economic institutions do not adhere to (and in fact, creatively devise) basic public health prevention strategies, admitting the need to reform themselves, many times at a financial loss, in order to protect the cities and communities around them. Similarly, such institutions cannot hope to implement novel and creative public health prevention strategies if they do not tackle the ideological polarization and misinformation present within their very own communities regarding Coronavirus. Most importantly, however, without open inquiries into how outbreaks start, and without transparency in reporting them, our social institutions, far from protecting our lives and the economy, will only act as massive conduits for transmitting the virus to the largely unaware communities inside and outside of them.

While it is important to stop the fires raging, it is equally important to not set new fires ablaze.

II. Universities in England and PHE: Big Business and National Politics in Local Areas

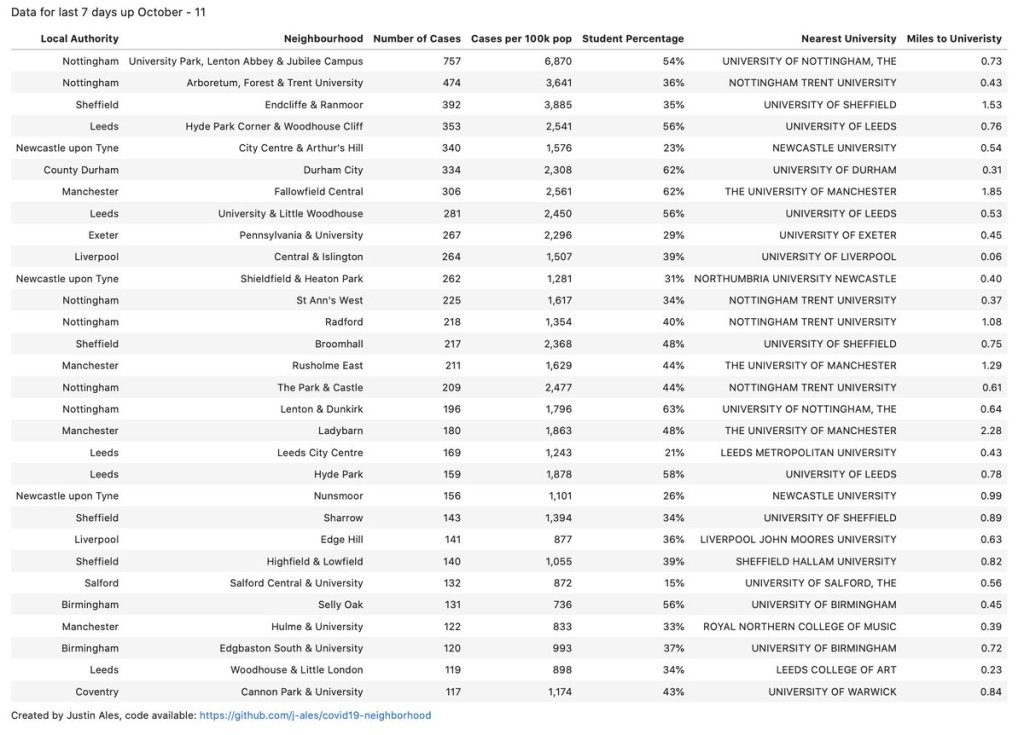

It is at this point that we have to talk about universities in England, as it is these that are at the heart of the new wave of Coronavirus cases that started in September and gained intensity and spread during the early part of October. Although no overall data has been released by the government or the Office for Students, the shocking rise in the number of cases in specific city areas clearly identified as representing areas of student accommodation (and in the span of only a week or two from the start of the term), leave little room for doubt:

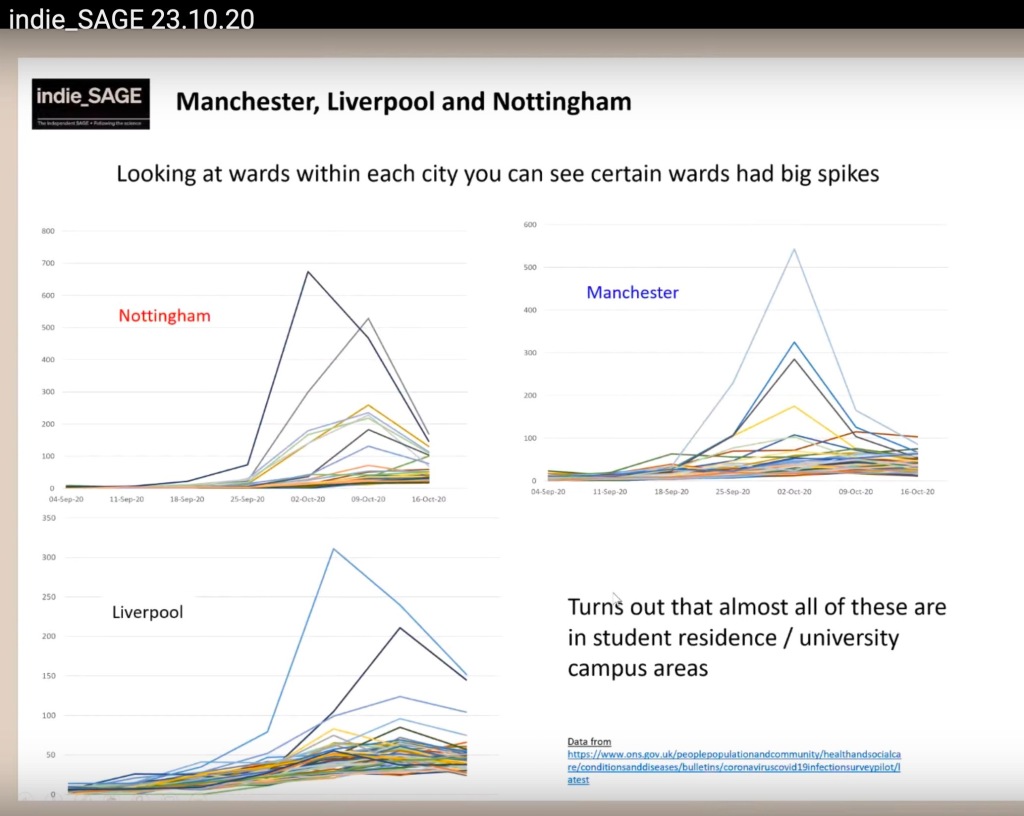

This is a chart that the Independent SAGE had used on the 23rd of October as an example of how almost all those wards that had seen big spikes since September are in student residence or university campus areas:

That the highest numbers of cases in England have generally appeared in those cities hosting two large-size universities (the exception to the rule apparently being London) points to a similar explanation.

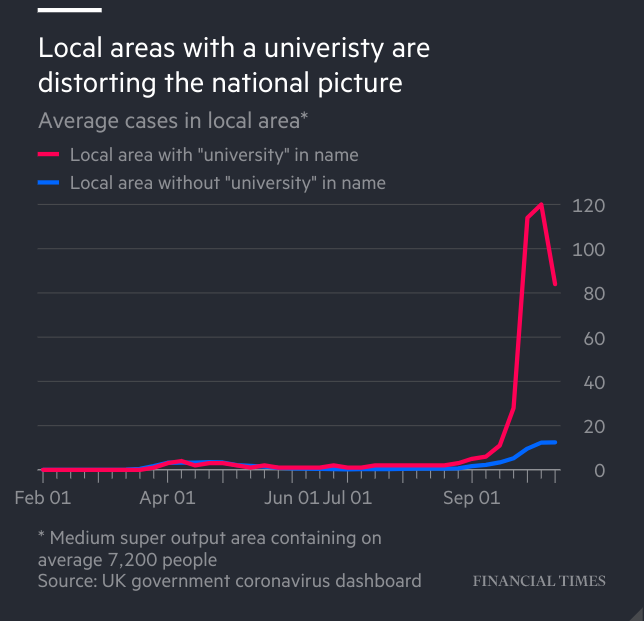

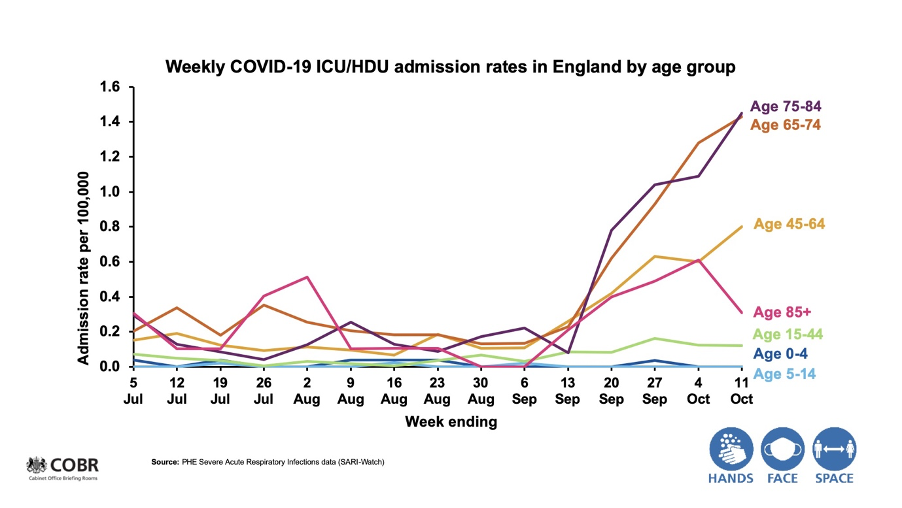

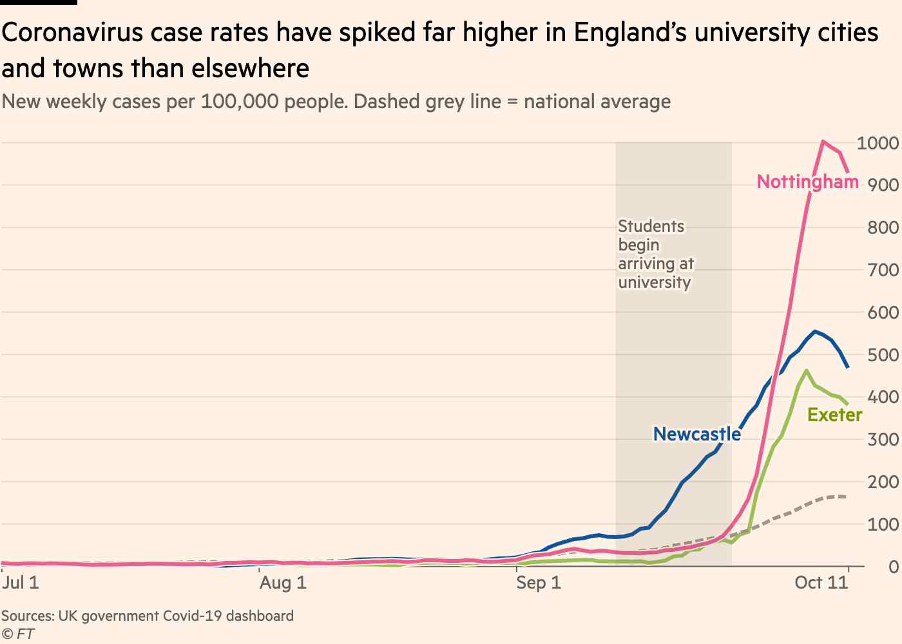

The following chart from the FT shows quite clearly that, after the start of term, local areas with a university have seen much higher numbers of cases than local areas without a university:

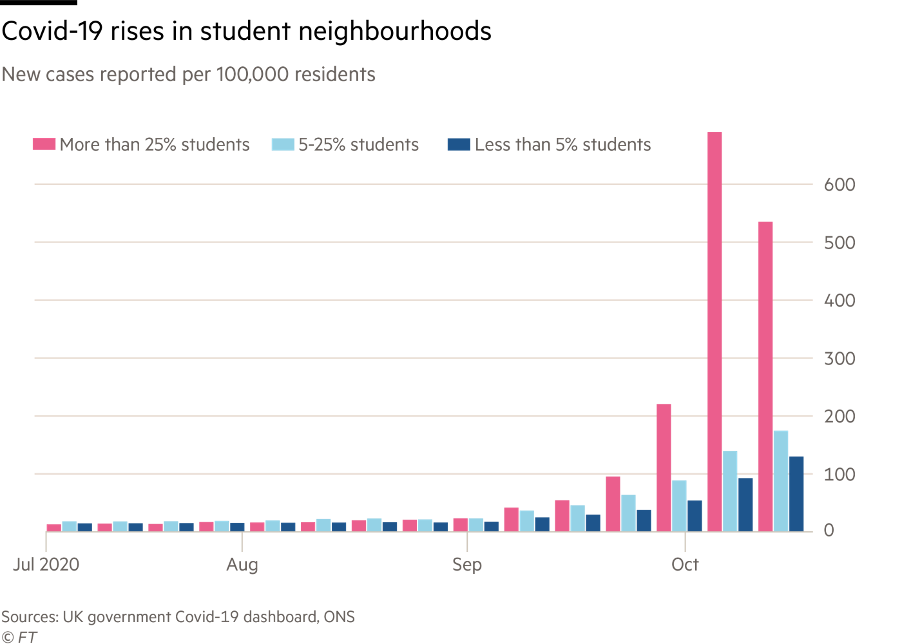

A similar chart, but with more specific information about student populated neighbourhoods, confirms the information above:

A more recent chart, from the 23rd of October, shows how the rise in Covid-19 cases coincided with the opening of schools and its explosive rise with the opening of universities:

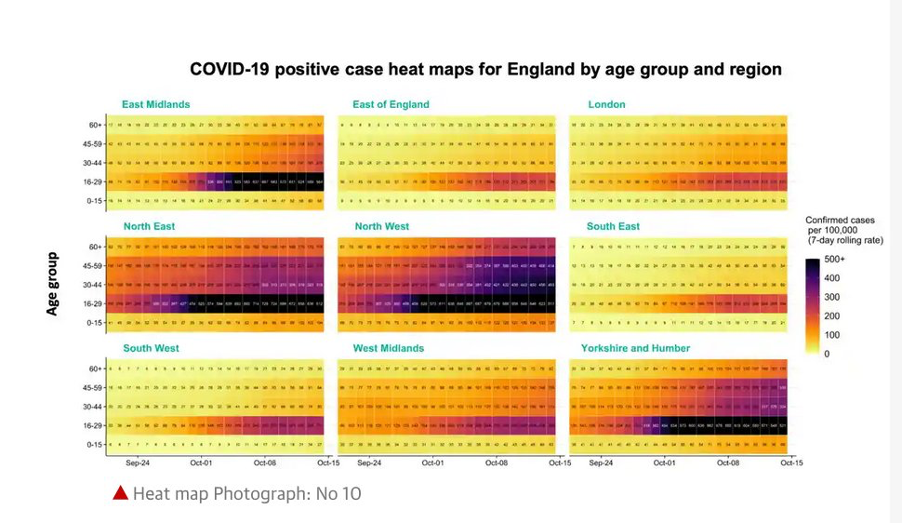

In another chart, released by England’s deputy chief medical officer Jonathan Van-Tam on the 12th of October, we can see how, from late September to the middle of October, most of the rise in cases nationally had been in the ages 16-29.

And yet another chart shows us how the numbers of Covid-19 hospitalizations has started rising in all age groups precisely from the start of term in schools and Universities, with numbers multiplying week after week:

The rise and subsequent increases in ICU/HDU admissions rates in England in ages 45-84 can be similarly matched with the start of term in schools and universities:

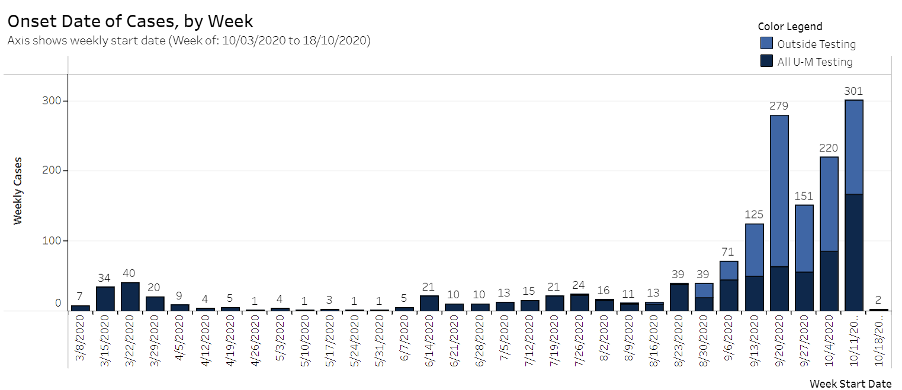

Unlike Scotland, where universities generally began their term a week or so earlier, most universities in England commenced their term on the 21st of September, for freshers, and on the 28th of September, for returners (second and third year undergraduate students plus postgraduate students), with their teaching starting on the 5th of October (The University of Oxford is one exception here, with their start of term scheduled only for the 11th of October).

Nothing is clear cut with universities, as some student cohorts arrive earlier and some later. However, it can be assumed that freshers arrived in their accommodation during the first two weeks prior to term, meaning between the 7th and the 14th of September (with some arriving even one week earlier), with most of the returners arriving between the 14th and the 21st of September (and some the week after).

Although the reporting of Covid-19 cases by different universities does not seem to be entirely transparent (and a considerable proportion of NHS test results might have been delayed by a week to 9 days) the ‘Timeline of cases by institution’ UCU graph is useful in showing that most of the first big rise in Covid-19 cases at English universities so far has been reported between the 28th of September and the 12th of October. Considering the delays in returning Pillar 2 test results and how difficult booking a test with the NHS has been during the same period, that freshers would not have been exactly prepared and willing to book a test, and that the incubation period for Covid-19 is set at 1-14 days (with an average incubation period of 5 days), we can only infer that students became infected with the virus almost immediately upon arriving in their accommodation. How can that be, considering all the preparations, assurances and advertising the universities have done in order to create a Covid-19 free environment?

On the 23rd of September, Professor of Global Health at the University of Edinburgh and Scottish Government adviser Devi Sridhar announced publicly on Twitter:

“Scotland now having significant outbreaks & large clusters within universities since they re-opened last week.”

Exactly the same can be said now about universities in England, or rather, exactly the same should have been publicly said around the 28th of September, a week after most English universities had officially opened on the 21st of September. It is no coincidence in my view that SAGE had recommended a circuit-breaker on exactly the 21st of September, with the additional intervention: “All university and college teaching to be online unless absolutely essential.” (An interesting aside fact – the numbers of positive Covid-19 cases in sizeable Scottish universities with large campuses have been considerably and consistently lower than those at English universities, if we look at the ‘Timeline of cases by institution’ UCU graph).

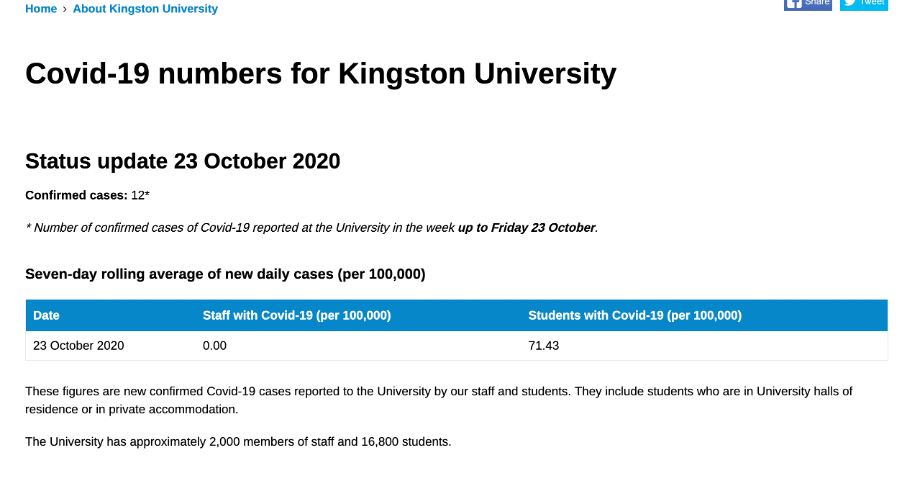

Notice that no national, regional or local Public Health England authority, from the many keeping daily oversight over the re-opening of universities (re-opening proceeding according to plans they have been supervising since July), has issued any similar statement. I am referring here, in particular, to the Director of Public Health in any given local authority, together with the PHE health protection teams – the local/regional part of PHE tasked with making risk assessments, continuous monitoring of available data, identifying transmission, defining, controlling and managing outbreaks and reducing transmission, and, also essentially, with informing the local authorities (county, district, borough and city councils) and the general public about the timing, location and number of Covid-19 cases.

Instead, it took more than 2-3 weeks for some of the Directors of Public Health in different local authorities to even admit some kind of ‘controllable’ outbreak was present in their local universities, and this only happened after repeated statements that the outbreak is “among the general population,” and that cases are “rising everywhere in the county” or “in all districts.” And when they did admit to the fact, they did so in a veiled manner, either by stating that the data shows that “higher infection rates are now being seen in young people aged 16 to 24” or by offering assurances that there is no evidence of wider community transmission. Considering that by the 28th of September it had become obvious to both universities and PHE that potentially massive Covid-19 outbreaks were underway on campuses at 45 universities it is remarkable that on the 29th of September Sky News could report the following:

“Some universities have been told not to release the number of cases by public health officials.

A spokesperson for the University of Nottingham told Sky News: “Regional Public Health England is currently asking us not to release institutional data for a couple of reasons – they are keen not to confuse their formal weekly data releases but they are also mindful of undermining the message that in the East Midlands, COVID-19 is affecting all demographics and so all demographics should have responsibility to protect health and follow the rules.

We are continuing to press the argument to PHE that we should be able to release data.”

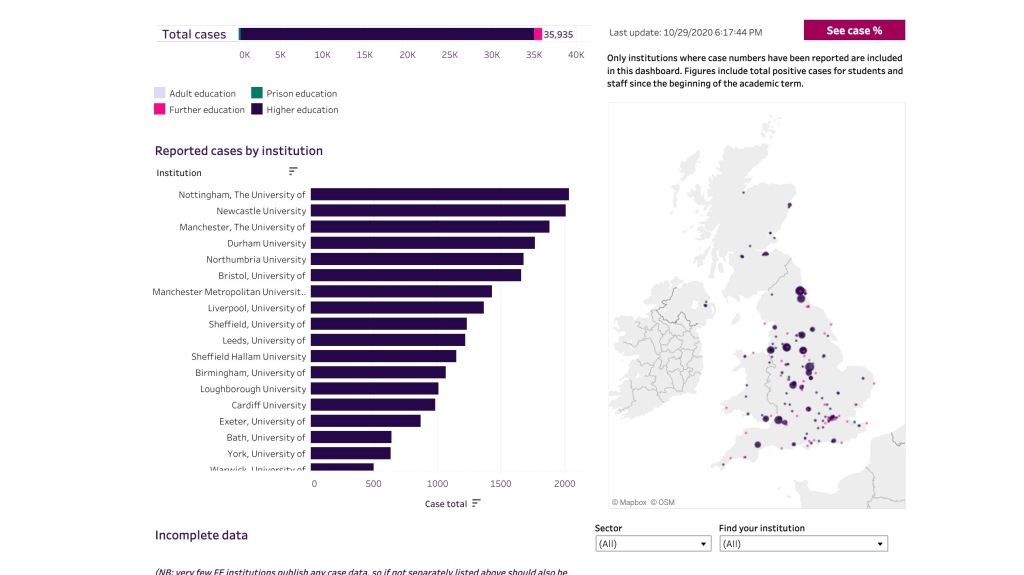

Even stranger here is the widely reported IT failure that managed to lose track of 15,841 Covid-19 positive cases (considered “non-complex cases,” that is, cases that were tested in community settings, rather than in hospitals or care homes – so presumably, also in university settings) between the 25th of September and the 2nd of October – period coinciding precisely with the week in which the first huge rises in positive cases of Covid-19 would have been observed at English universities but also with the days and weeks after SAGE had advised for the introduction of a circuit breaker lockdown. The fact that the Health Secretary Matt Hancock later told MPs that “outbreak control in care homes, schools and hospitals had not been directly affected, as they do not rely on the data in question” should make us wonder if the lost data did not in fact concern UK universities. For the week after, from the 5th to the 11th of October, the government would later report 9,000 cases of Covid-19 amongst students in the UK, with the numbers spread between 68 campuses across the country. Less than a week later from that, on the 17th of October, the UCU dashboard reported 20,172 cases of Covid-19 in UK higher education, while UniCovid UK “put[] the number of confirmed cases for students at 20,782, for staff 333, in total 21,115,” with 115 universities reporting such cases (93 in England, 1 in Northern Ireland, 14 in Scotland and 7 in Wales). Also on the same day, The Guardian reported the following, a snapshot of the state of affairs that had generally characterized early responses of English universities in the week from the 21st of September to the 28th of September, before resulting in them developing massive outbreaks: “A lecturer at Bournemouth University, who wants to be anonymous, is angry that the university has not made its Covid numbers public. ‘Every single student hall at Bournemouth has cases, from a single isolation, to a whole corridor. There are more than 100 cases but the management thinks this should be kept confidential.’”

It is exactly such instances of delay, silence and obfuscation from both PHE and universities (and one must count here the week/s in which the number of cases were low but many cases of isolation existed, and the prior weeks in which knowledge of patterns of socialization that would greatly spread the virus had been widely observable) that is responsible for the transmission of the outbreak in many other parts of the wider community. After having waited for several weeks of widespread transmission, one could indeed claim relatively unopposed that the outbreak is among the general population and rising everywhere.

It is easy to see how such a course of action might have, quite comfortably and conveniently, excluded both universities and the government from any further scrutiny, with the focus of restrictions being placed instead onto the working class, local communities and businesses, and places such as pubs, bars and restaurants, a public scandal now diverting attention even further away. (This is not to deny that places such as pubs, bars and restaurants were probably an important secondary transmission avenue for university outbreaks reaching the wider community, but can anybody truly say they were the ground zero and the primary sources for these latest mass outbreaks in the country?)

This silence or misdirection points to another question asked in every city or region that has seen a sharp outbreak of Coronavirus in the period 21st September to the 10th of October, but which almost no one seeks to answer: where did the local outbreak originate? Where is the origin of the outbreak? Where did the transmission spread from? What has caused this potential second wave?

That local newspapers and local councils did not seek an answer to this question testifies both to the political influence of the Directors of Public Health and of PHE and to the amazing influence of powerful universities on local mass-media and local councils. It is this power dimension of universities as both state-agents and private commercial entities that, in many cases, cannot be held accountable by any city, local or regional authorities, that is undertheorized and naively overlooked. The role of private accommodation providers accounting for half of student bed spaces in the UK based on 2018 research by Unipol and the National Union of Students (NUS) also needs more scrutiny.[1]

[1] It might well be that in some cities PHE, the local authorities (and/or some of the key local businesses) and universities had commonly agreed, even before the start of term, that students were too important for the local economy to let anything impede their arrival and stay on campus and in the city, although the contestations and surprise of local city councillors during the outbreaks generally show otherwise. Even in the case of such a possibility, however, the clear and almost wilful ignorance by universities and PHE of the most basic public health guidelines (to be discussed below), their joined actions to delay the news becoming public and their failure to properly address the root causes of outbreaks would have put the health of both the university community and of larger local communities at risk, while also heavily impacting on the local economy (because of the very probable later imposition of measures such as a tier 2 or 3 lockdown or a local circuit breaker). When considered in terms of their impact at national scale, such actions would have been exponentially riskier and massively self-defeating, because of the threat of a nation-wide second wave like the one experienced in April, with all the effects associated with it. While such actions would have been an affront to the very notion of efficiency at both the economic and political level (bringing a huge cost to both the university and to the government), a massive undermining of democracy, and a most vile threat to the health of the general public, it cannot be said, however, that more important private interests amongst the higher levels of the university and of the private accommodation sector, as well as more significant political interests of the national government, would not have been safeguarded, through the very same measures, in the short term.

That presumably the University of Exeter has publicly confirmed that “more than 80% of coronavirus cases in one of the worst affected cities [namely, Exeter] are attributable to students,” is spectacularly unique, though less surprising now, considering the more recent need to counter a potential lockdown by emphasizing that any major outbreak is localized and could be contained.

As far as I am aware, the first article to really look at this question appeared in The Times (a daily national newspaper) on the 9th of October, and was written by Data Journalist Ryan Watts and edited by Chris Smyth. The article did not seek to identify the origin of the second wave of Coronavirus, but suggested that “universities are amplifying the epidemic” and established that “of the 20 areas with the highest infection rates, 11 were student neighbourhoods” (in Manchester, Leeds, Newcastle, Sheffield, Nottingham and Liverpool, etc.) and 6 others, student heavy areas (Nottingham and Manchester, etc.). This analysis was based on data about the entire population that tested positive for the virus in the week to October 2. Its conclusion was measured but poignant: “Most of the areas with the highest infection rates in recent weeks are dominated by students, raising questions about how the return to campus has been managed.”

In the same article, the secretary of the University and College Union, Jo Grady, who had warned about such dangers on the 29th of August , 31st of August, and on the 14th -17th of September, was also cited as stating that the recent ‘spikes’ were “a predictable and preventable crisis that ministers and universities chose not to do more to constrain.” As far as I am aware the first time an explicit link was made between England’s rise in Coronavirus cases and the start of term at Universities in England was in the FT on the 22nd of October (a month later from the official start of term, time throughout which the virus had been spreading mostly unhindered), through the chart below:

It is quite widely known now that in-depth and specific warnings about the rise of Covid-19 in UK universities, and about the measures needed to prevent them, had been offered earlier not only by the UCU and the Independent SAGE, but also by Gavin Yamey in the British Medical Journal. In addition to these, the 21st of September advice from the SAGE urging ministers to impose “a circuit breaker lockdown,” have everybody work from home where possible, and move all university and college teaching online, has also been and continues to be largely ignored by both the government and a large number of universities with very high or substantial numbers of Covid-19 cases.

How can it be, then, that the partnerships between PHE and English universities led to mass outbreaks developing so quickly and in so many university campuses at the very start of term?

This is the question around which any current analysis of the current higher education system in England must revolve. While the topic of the post-pandemic university is one admirably covered in the academic community and which could have many facets and bear many fruits into the long-term future, I would suggest that ‘the pandemic university,’ meaning, research into the Covid-19 crisis now unfolding in English universities, should maybe be given priority for the time being. Until that time, I can only emphasize certain major operational failures and their probable underpinning rationales as the reasons why so many English universities have failed to prevent Covid-19 mass outbreaks and are now failing to stop their transmission into the wider community.

III. Operational Failures

III.1. Centralization, financialization, and the drive for efficiency in University Halls of Residence over a period of ten years

Until the late 2000s most universities still displayed a form of organization for their student halls that was reminiscent, though not identical, with the structure of the Residential College developed by Durham University in the 19th century. The Durham model of the Residential College deviated from the models of Oxford and Cambridge by creating colleges that were only residential, but which, despite some degree of autonomy, functioned under the central administration. In the Oxbridge model, colleges had been both residential and teaching institutions with considerable legal autonomy and independence from the University. In today’s terms, the Oxbridge model saw student accommodation (or the student halls) as the natural extension of the academic divisions and their specific academic departments, with residential colleges “ultimately responsible for selecting and admitting their undergraduate students” and offering tutorial teaching for undergraduates. In the Oxbridge system one can still choose their residential college based on the courses available for that college, which is obviously not how we think of student accommodation nowadays. Educationally, this model made a lot of sense because it integrated academic life with all aspects of student life, by drawing the undergraduate students closer to the postgraduate students and to the junior and senior academics in the same fields, thus creating a truly academic community [of course, in such a set-up senior academics would have held an enormous amount of influence (both positive and negative) compared to their influence in most universities today].

The Durham model continued this same model by severing most of the links between Faculties or Departments and the Residential College and bringing the student halls under the control of the central administration. In semblance, administrative organization, pomp and rituals, however, the Durham college retained the same model: “Each of the Durham colleges has the standard configuration: a master or principal at the head, a senior tutor who is responsible for advising and welfare, a body of senior members (fellows and tutors), and a body of junior members (undergraduates and graduate students). A complete compliment of supporting facilities is present in each college: offices and reception space, a senior common room for the fellows and tutors, a junior common room–bar–game room combination, a library, and a spacious dining hall. One of the pleasures of touring the Durham colleges last month was seeing residential college buildings that were designed by people who understood the collegiate idea. The placement of offices, the landscaping of the courtyards, the configuration of the dining halls and common rooms—all these things bespoke a deep understanding of how architecture supports communal life.”

The Durham residential college model was also adopted in the late 1960s by the University of Kent, Lancaster University and the University of York. All other English universities copied the same model described in the quotation just above but eliminated the very notion of the residential college, and of its relative independence, and streamlined its organizational structure to fit with the demands and purview of central administration. The result of this process were the “University halls of residence” as we knew them prior to 2010 (that is, before the fall-out from the financial crisis of 2008).

Prior to 2010 the University Halls of Residence still retained an organizational structure reminiscent of the Durham (and indeed Oxbridge) collegiate model. Each Hall of Residence was run by a Warden (usually a Senior Lecturer) and a deputy Warden (usually a Junior Lecturer) assisted by a team of Senior Residents (postgraduate students in general, but usually PhD students, who could later become Wardens). In other universities, the titles differed but the scheme was similar: Wardens, Vice-Wardens (Senior Members or Senior tutors), and Resident tutors. Oftentimes Wardens served for more than ten years in their role (Vice-Wardens served for extended periods too), continuing a tradition many decades old, which means this organization system ensured those in key roles had considerable experience in pastoral roles, the organization of student life, welfare and disciplinary matters, and even some degree of say in related university policies. For each of the Halls, the Warden was assisted by a Secretary, a Hall Manager, an Assistant Manager, Porters, a catering/bar team and a cleaning team, etc. All the Hall administrative personnel worked very closely with the Security team at the University.

Since 2010 this organizational model for the University Halls of Residence has been under attack from several directions (although, it still continues to this day in some universities):

Model A.

Probably, the most widespread tendency has been to remove the roles of the Warden and Vice-Warden and maintain only a reduced number of Senior Residents, thus effectively removing the pastoral teams out of the halls. In the old system, and the new system has retained this feature, Senior Residents were available in shifts, with each of them available on duty for 24 hours (meaning, primarily responsible for the entire Hall at night-time) approximately one day per week, but only during term-time.

In the most radical version of this new system, the Senior Resident role, once only open to postgraduate students, became geared towards second and third-year undergraduate students (and away from PhD students), known as Residence or Resident Assistants/Advisors or as Residence Life Mentors. Referred to Residence Life Coordinators administrative staff at the university holding an undergraduate degree [“Education: Bachelor’s (Required)”] and few years of administrative experience, were then recruited to manage such teams.

While extremely popular, this version of the model did not apply everywhere the same way. One interesting variation, for example, is the University of Manchester, which developed a more complex structure in which ResLife Advisors (not Assistants), still recruited only from the ranks of postgraduate students or staff, were led by Res/Life Officers (one per Hall), with all of them headed by a ResLife Manager and a team of three ResLife Coordinators (though the Manager and Coordinators were still recruited from within the ranks of administrative staff holding an undergraduate degree) – an interesting set-up where staff with an undergraduate degree manage a team of postgraduate students. Another variation is Bristol, where the Wardens and Duty-Wardens were removed but where the role of Chief Residents was reserved generally for postgraduate students, with the role of Senior Residents geared towards second and third-year undergraduates, both of them reporting to a Residential Life Adviser coordinating a cluster of residences. In the Bristol system, all these roles are part-time. It is not clear what educational and administrative criteria a Residential Life Adviser must meet except for having “previous experience and qualifications in the provision of mental health and wellbeing support.”

Such a reorganization at Bristol University, it has been reported in 2017, would have been expected to “result in savings of £800,000.” It should be understood here, that since the Wardens and Vice-Wardens sat on a number of University Committees (including Hall Committees or Councils that included members of the University Council and Senate etc.), with Senior Residents from all Halls usually also having their own President and Senior Residents’ committee – this organizational change would have erased, in one single stroke, all those intermediate bodies and committees acting as a somewhat autonomous and more democratic interface between the students and academics and the central administration of the university. This, by the way, is the main reason why the majority of academics in many universities had no inkling of what was happening in University Student Halls at the start of term in relation to the Covid-19 pandemic, reason for which they were unable to foresee and raise specific concerns, issue specific warnings or hold anyone accountable, before the outbreaks had occurred, and sometimes, even in their aftermath.

We are, of course, not talking here only about making cuts and the removal of pastoral services out of the halls (or their almost complete erosion) but also about their centralization and financialization.

Centralization as the removal of any influence academic structures/academic identity might have had on student accommodation but also as the replacing of a relatively decentralized system in which each Hall had its own administration, with a top-down one, in which several Halls share a single Hall’s administration team directly affiliated with a centralized management authority, itself part of the central administration of the university.

Financialization, because of mainly four reasons:

1) because Hall managers newly employed from the private sector (usually hospitality) streamlined and centralized Hall services etc., by retaining a very small number of core workers (porters, cleaners, catering staff etc.), if at all, on reduced contracts, while relying on outsourcing (temporary work on zero-hours contracts) when faced with more demand.

2) because of the introduction of bonuses based on the amount of savings made to the budgets available to managers in Professional Services from top to bottom, meaning from the Registrar, to the Director for the Student Experience, to the Director of Residential Services and so forth, down to the Hall Manager (or down the different levels of similar organizational hierarchical structures);

3) because the role of Hall managers is not only to offer a service to students but to maximize profits by renting accommodation to companies and organizations outside of student term or whenever else possible;

4) because part of the student accommodation at Universities (usually the self-catered halls) has been privatized through outsourcing or private-public partnerships with private companies involved in both building and administering what is known as “purpose built student accommodation” (PBSA). Such properties usually take two forms:

An understanding of PBSA is essential to the understanding of Model A or the Residential Life Services Model.

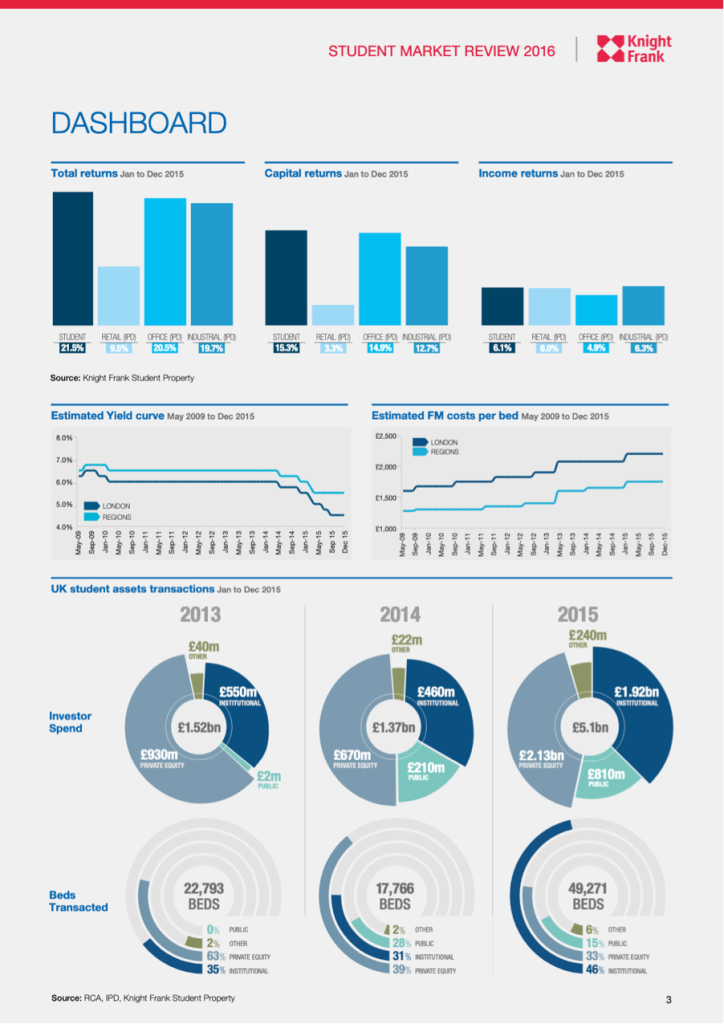

Unite Students, UPP and Blackstone (who recently bought IQ from Goldman Sachs and the health research charity Wellcome Trust for £4.7bn) are the largest partnership providers of student accommodation in the country and PBSA is an investment market with a total transaction volume of approximately £4bn in 2019 according to the 2019 Cushman & Wakefield report.

PBSA, a global booming sector in US and the UK until the pandemic, is part of the reason why the Residential Life Services Model has been preferred to the former model derived from the Durham University Collegiate System in a process that has seen a marked increase in the financialization of HE in the UK during the last decade:

“Investors such as private equity firms and Goldman have been piling into purpose-built student housing in recent years, as demand continues to outstrip the number of beds provided by 30%.”

A clear reason for this is that the return on PBSA investment, estimated by some at 5% per year, is actually as high as 20% when the income returns from students are added the capital increase in the value of the property (capital return = the part of the return from an asset that is delivered purely through change in the price of that asset.)

This is described in the dashboard provided below:

Such private-public partnerships are also the reason why the role of Residence Life Coordinator has taken on completely new dimensions when compared to any similar role in any of the previous models. The PBSA Residence Life Coordinator Role differs immensely even from the same role offered through the same Residential Life Model, when the model is being operated by the University alone. Compare, for example, the Residence Life Coordinator job description for UPP & University of Reading, with that for UPP & NTU (Nottingham Trent University), and then contrast those with the same job description when the Residence Life Model is run by a University alone.

These are just some novel features of the University &UPP Residence Life Coordinator job descriptions mentioned above:

– “Run Tell Us events gathering specific information from students to target/prevent any problems that might be mentioned in the Customer Satisfaction Survey and anecdotally”

– “Manage the h@h (Halls at Home) mobile app events and news article components.”

– “Manage all h@h student facing social media platforms.”

– “Write feedback reports and present findings to, NTU Student experience group, site management and the wider business.”

– “This role will include some evening and weekend working.”

– “The role is responsible for the implementation of the home at halls residence life programme, recruiting and managing student staff and volunteers and gathering student feedback to inform future planning.”

– “Review competitors’ facilities and services” (This criterion is only present in the UPP&University of Reading job description).

Overall, this new model, the Residential Life Services Model as it is called at Bristol University, or Residential Life/ResLife, as it is called at the University of Manchester, Newcastle University, University of Sheffield, University of Leeds, University of Exeter, is what has replaced the University Halls of Residence Model in quite a number of HE institutions. I have singled these institutions out because, at this point in time (the 16th of October), they constitute six of the top ten universities with the highest numbers of Covid-19 cases in UK higher education, judging by the UCU Covid-19 dashboard.

We can see now why universities that had replaced the model of the University Halls of Residence after 2010 (which, in truth, represented only a shadow of the collegiate system at Durham University that itself constituted only a weakened copy of the Oxbridge model) with the Residential Life Services Model would have been much less prepared to face a pandemic.

Considering that many thousands of students live in student accommodation, to leave day-to-day monitoring and disciplinary matters effectively in the hands of undergraduate students is a shameful dereliction of the duty of care and a psychological burden that no second or third-year undergraduate student should have to carry. One should really wonder how such young students[1] would have been pushed onto the frontlines of the Covid-19 outbreak in this way, in addition to being made responsible for dealing with the serious problems that generally affect student halls (alcohol, robberies, drugs, fighting, sexual violence, mental health, suicide). It is almost as if we were purposefully aiming to damage them. What authority would one or even several second-year students have over tens or even hundreds of rowdy freshers on a big night? Similarly, no matter how conscientious, lower administrative staff with an undergraduate degree could never have the same experience in offering pastoral support, in making themselves heard and understood by students, or the same say in alerting, informing or even challenging the different bodies of the university, when compared to academics with many years of previous experience in teaching/research/administration and in the role of Wardens. There is also a huge issue of numbers. Previously, each Hall had been managed by a Warden with a Deputy-Warden and their entire Hall team, with each Senior Resident directly responsible for a section of a block or for a block. In the ResLife model, the numbers of staff have generally been considerably reduced, with both the Residence Life Coordinator and the Residence Assistants/Advisors sometimes responsible for many times more the number of Halls (called ‘villages’ or ‘clusters’ etc) and students than in the past. Or, if their numbers have not been reduced, then, their hours have been. Similarly, these roles have now been tasked with an increased responsibility and active duty to gather information, predict, report and prevent any sensitive information about the failures of the university, or of their PBSA partners, from reaching other university channels or communities, social media platforms or the general public.

[1] This job description (within catered Halls, the duties of the Senior Resident would be the same with those of the Residential Adviser) provides a good insight into what the duties of such undergraduate students in this system are:

- “The Residential Adviser will help promote and maintain a peaceful environment that the students can enjoy.

- The Residential Adviser provides pastoral care and basic welfare advice and sign posting to relevant support services (both internal and external) to their students.

- The Residential Adviser assists in a wide range of tasks that ensure the smooth operation of the Halls and the Hall community.

- The Residential Adviser will be the first responder on hand to deal with emergencies and serious incidents arising during their on-call duty nights – as such they will be the first point of contact for Students, Emergency Services, Campus Support and members of the local community.

- The Residential Adviser will often need to make on-the-spot decisions to take definitive action, to contact the Warden, to call emergency services or other appropriate authority.”

Such a system was never meant to adequately deal with even the general pastoral issues of the day, not to mention having to deal with a pandemic. What is even more shocking is that this system was not reformed and reinforced in the first six months of the pandemic so that it would stand a better chance against the pandemic at the start of the new academic year.

At this point, one could remark that some of the universities that do not rely on the Residential Life Services Model are also showing a high or a considerable number of Covid-19 cases. Amongst them, Durham University – an exemplar of the Collegiate system. There are four things I would say here. The first is that even the Collegiate system could be rendered ineffective through cuts and restructuring. The second is that there still are other ways in which a University could have gotten their response to Coronavirus seriously wrong (to be discussed next). Third, most other universities that follow the Collegiate model are still doing relatively well in the UCU Covid-19 case dashboard.

Last but not least, some of the universities that have held onto the pre-2010 University Halls of Residence model have seriously altered and weakened this system, in ways that resemble, at least partially, the Residential Life Services model. This reorganization constitutes the second modality through which the organizational model of the University Halls of Residence has come under attack since 2010.

Model B.

In this version, the University Halls of Residence model was restructured in two ways:

1. Firstly, for catered Halls, cuts were made so that the same Hall team (Warden, Duty-Warden, Senior Residents or Resident Tutors, Hall Manager and/or Hall Assistant-Manager, Hall Secretary, Hall Porter, Hall Catering Team, Hall Cleaning Team, Hall Bar team etc.) previously responsible for a single Hall, was now left in charge of 3 or 4 such Halls, grouped together into ‘villages’ or ‘clusters.’ Next, as with the Residential Life Services model, the number of Senior Residents was cut, and their role geared towards second and third year undergraduate students. While this system did not take pastoral care out of the Halls, it nevertheless weakened it by rendering it so thin as to become largely inefficient. The reliance of such models on second year undergraduate students (deployed to the frontlines even in times of crisis) has already been critiqued before. The same critique stands here.

While in this system these undergraduate students could theoretically benefit from adequate mentorship and support, the issue, however, is that at every level, be it that of Warden or Senior Resident, the system is overburdened, overstretched and, thus, easily overwhelmed.

2. Secondly, the private-public Unite Students/UPP/IQ etc. & Universities model (or the PBSA model), which as discussed previously, is the more streamlined and radical version of the Residential Life Services Model, relying only on Residential Life Coordinators (Bachelor’s required) and Resident Assistants (usually second or third year undergraduate students), became the mode of organization for self-catered Halls, thus challenging the existent University Halls of Residence model from within. Some universities, like Oxford Brookes, for example, seem to be running entirely on this type of PBSA system, having entered partnerships with “third party residence providers” such as “Unite Students Ltd, CRM Students Ltd, A2Dominion and Host.”

This dual-model, with the first half, a cheap version of the pre-2010 University Halls of Residence Model, and the second half, the radical version of the Residential Life Services Model, in other words, the worst of both worlds from a pastoral care dimension, seems to characterize institutions such as the University of Nottingham and the University of Reading.

Less advanced in its transition towards such a model, the University of Liverpool seems to have retained a larger part of the pre-2010 University Halls of Residence Model, with one Warden (recruited from Faculty) per Hall (although Residential Advisers can now also be recruited from the ranks of undergraduate students). The same seems to apply to the University of Glasgow.

Model C.

Finally, some universities, such as UCL, the University of Warwick and Loughborough University seem to have been able to retain the pre-2010 University Halls of Residence Model, with Wardens recruited from Faculty and Student Residence Advisors recruited only from the postgraduate student community.

Assigning Responsibility:

In all these three cases (Models A, B, and C) the responsibility for decision-making regarding the running and administration of student accommodation rests with the same higher levels of the university. Let us take a quick look at the three universities with most Covid-19 cases in the UK since the start of term, as reported by the UCU Covid-19 dashboard. For the University of Manchester, it is the Registrar, from which responsibility flows downward to the Director for the Student Experience, and then to the Director of Residential Services. Obvious from the webpages shared here, the same centralized leadership now covers areas of student life and academic services that once had belonged to Schools/Departments or to more decentralized, semi-autonomous structures.

“The Directorate for the Student Experience (DSE),” we are thus told, “was established to facilitate a joined up approach to the delivery of services to students throughout the student lifecycle and to provide leadership to enhance the student experience. The DSE is made up of 5 divisions, and a central Directorate Office:”

For the University of Newcastle it is again the Registrar (both Risk Management and Emergency Response are also areas under this role) but also the Executive Board, while for the University of Nottingham it is again the Registrar, in a structure that seems to show a remarkable degree of centralization, and in which both Residence Life (Pastoral Care/Wardens and Tutors) and Campus Life fall explicitly under the Registrar’s responsibility:

In contrast with the first three examples, the UCL governance structure is much more complex and possibly more decentralized, with the Registrar not nearly as significant a role as in the other cases (for example, if compared with the role of the Chief Operating Officer, of the Director of Estates, or with the roles of other Heads of Professional Services).

III.2. Not heeding the warnings that University Student Halls could be like Cruise Ships for Coronavirus

This point was extremely clearly explained in a Time article from 16 July 2020 by Katie Mack and Gavin Yamey:

<<Research has shown that air flow can transmit aerosolized SARS-Cov-2 much further than 6 feet. In the absence of constant and efficient ventilation, viral particles can remain airborne for at least 3 hours. In most universities, opening all the windows and doors would be impractical or impossible, and air conditioning systems can waft recycled air over occupants for hours. Masks help, but they’re not perfect protection.

Not surprisingly, many professors, particularly those who are older or have pre-existing medical conditions, say they will refuse to teach inside classrooms. But to be able to refuse, you need some degree of power. There’s a real risk that so-called contingent faculty, those in “insecure, unsupported positions with little job security and few protections for academic freedom” will have no choice—they will feel pressured to teach in person or be replaced.

Beyond the classroom, colleges and universities are ‘congregate settings’ that are known to create high risk for viral transmission, akin to nursing homes or cruise ships. The campus experience includes bringing students together in dormitories, dining halls, athletic training, parties, bars and clubs—gatherings that would risk becoming ‘superspreading events.’ …

For the city where a campus is based, reopening will be like dropping a cruise ship into the center of town—and giving passengers free rein. Campus outbreaks cannot be hermetically sealed—they will inevitably cause a spike in community spread, affecting the city, state, and beyond. Universities that fully re-open in the midst of an uncontrolled epidemic will bear responsibility for the damage they cause to their wider communities. [my emphasis]>>

However, it will be wrong to suggest that one would need to read some expert advice in order to foresee the real dangers that University Student Halls were likely to face in the case of a pandemic like Covid-19. Just the layout and location of the University Student Halls tells the whole story. With each major University having between 7 to 14 Student Halls (with most comprising 200 to 300 students but sometimes even going as high as having over 1000 students) on any one of their several campuses, all in very close location to each other and sharing the same urban and green spaces, and thus, giving the opportunity for thousands to socialize day and night (a unique and special opportunity after 6 months of lockdown), would it have been really hard to predict that student halls in October would very much operate just like cruise-ships in terms of spreading the virus?

After all, the BMJ had warned before the start of term: “Many outbreaks in US universities have been in congregate settings—such as dorms and off-campus housing—pointing to a third lesson. Viral transmission between asymptomatic students can occur at lightning speed in these settings.” Despite this, leading figures in UK HE still contend nowadays that the warnings about US universities and Covid-19 were never truly applicable to the UK, while simultaneously offering statements such as this: “However, I would honestly say I think the speed of transmission both within student halls and in off-campus settings took many, including me, by surprise and coping with that has been a huge challenge for universities.”

No surprise then that the Fallowfield Campus – “‘the epicentre of the epicentre’ as one student puts it,” a phrase that could be repeated of many a campus in other cities, has become associated with not so flattering a term as “covid soup”. We know that universities understood some of these issues from the very beginning, because many had initially reported plans to spatially distance inhabited flats in the halls. Which brings us to the next point.

III.3. Some of the most important universities in the UK did not reduce the capacity of their student halls despite the need for physical distancing

As reported by BBC Scotland’s Disclosure programme:

“The programme found some universities cut the number of students in halls of residence by as much as half but St Andrews University, the University of Edinburgh and the Royal Conservatoire of Scotland, in Glasgow, were at full capacity. … Eight other universities would not tell the BBC whether or not they cut numbers to allow physical distancing.”

The eight universities that did not answer are: Aberdeen, Glasgow, Dundee, Heriot-Watt, Strathclyde, Stirling, Edinburgh Napier and Glasgow School of Art.

Not surprisingly, the explanation has much to do with the profitable PBSA sector and with how universities have left themselves exposed in terms of what they have agreed to with private accommodation providers. The key issue: having signed up for a certain percentage of the rooms (presumably, a quite high number) being filled each year.

This has been wonderfully reported below:

“The Disclosure investigation also found that some universities are subject to ‘nomination agreements’ with private accommodation providers.

This is where universities enter deals with private developers to provide modern attractive accommodation. These deals may include guarantees from universities that a certain percentage of the rooms will be filled each year.

For instance, the University of Edinburgh has eight nomination agreements in place, with a fifth of its students living in accommodation rented from private providers.

Financial analyst Louise Cooper told the programme that there had been an explosion of student numbers in recent years and universities had turned over their property portfolios to private developers.

But she said the ‘risk’ of the properties being empty was generally being borne by the universities.

‘The underlying model requires high occupancy, students in there, paying their weekly, monthly rents,’ she said. ‘As ever, you need to follow the money.’

The University of Edinburgh said: ‘Throughout the pandemic our prime concern has been, and remains, the health, safety and general well-being of our students and staff. This will always come before any financial considerations.’”

The situation is even more complex in English Universities. According to the Guardian, experts reported concern that “although UK universities have drastically scaled back face-to-face teaching so that campuses can run at around a third of their usual occupancy, many student halls are full.” According to the same article, English universities “blame the A-level fiasco for pushing them to maximum occupancy.” As the reporting goes:

“Vice-chancellors reacted with fury this week to threats by the education secretary, Gavin Williamson, to dock their bonuses because of what he called the Covid ‘crisis’ in universities. One, who asked not to be named, said: ‘The government looked to universities to sort out the post A-level mess. They pleaded with us to take students who met offers. They were not interested in capacity, social distancing on campus, pressures in halls or private dwellings. Suddenly they have forgotten all of that and now universities are the problem.”

Is that the full and only explanation for high to maximum occupancy in student accommodation on campus and around the city? Most likely not, but possibly in part a convenient way to highlight the role of the government in a blame game that universities have been carefully weighing (and some suggest, playing) from before the start of term.

III.4. Testing, Self-Isolation and Basics

Questions about testing and tracing and self-isolation are questions about the pandemic, about society, about politics and economics. They are incredibly complex questions and the ground is shifting daily. Surely, all we can do at any given moment is judge ourselves against the best knowledge of the time, and against a basic standard of pragmatism and creativity.

A strong argument can be made from city to city and region to region that unless transmission in the general community and in the community of the university (both with a functional system of test, track and trace) was low, Universities should have never considered to open their campuses and should have instead moved everything online:

“What would it take to re-open safely? We can look to Taiwan as an example. Rather than leaving individual universities to piece together their own plans, Taiwan’s Ministry of Education produced a national strategy for college campuses. The strategy included an initial quarantine, frequent testing of all students, sanitation, masks, distancing, reduction of student density, cleaning of dorms twice daily with bleach, and allowing only one student per dining table. It also included mandatory quarantine for anyone exposed, and infection-number thresholds at which an entire university would shut down. With this huge array of protective measures on campus, Taiwanese universities were able to reopen successfully and see a total of just seven confirmed university-based cases by June 18, and only four new cases nationwide since then.

Aside from the safety protocols more rigorous than any we’ve seen proposed in the U.S., Taiwan’s universities had another advantage America’s don’t: a well-controlled epidemic with virtually no community transmission. To date, Taiwan has had only 451 cases and seven deaths. Not a single state in the U.S. has had anything like that level of success.

In that context, it’s hard to see how any U.S. university could have a safe on-campus reopening plan comprehensive enough to succeed.

We understand the financial pressures that colleges and universities are facing. Some could risk bankruptcy without the revenue that reopening will generate. We also recognize the enormous benefits of campus life and in-person teaching and the wishes of some students and parents to experience these. But at what price?”

At the same time, to those arguing that life must go on, that universities have done all that they could do to re-open safely, and that nothing more could have been done, reply must be given that controlling the virus is always a choice and a possible outcome, as long as community transmission is low to start with, test, track and trace is working, and as long as basic public health strategies are being acknowledged (as Taiwan’s example shows).

I would argue that, in terms of public health, several considerations would have been obvious to university leaders many months before the start of the academic term in September, but that managerial failure to act on them has led to the present crisis:

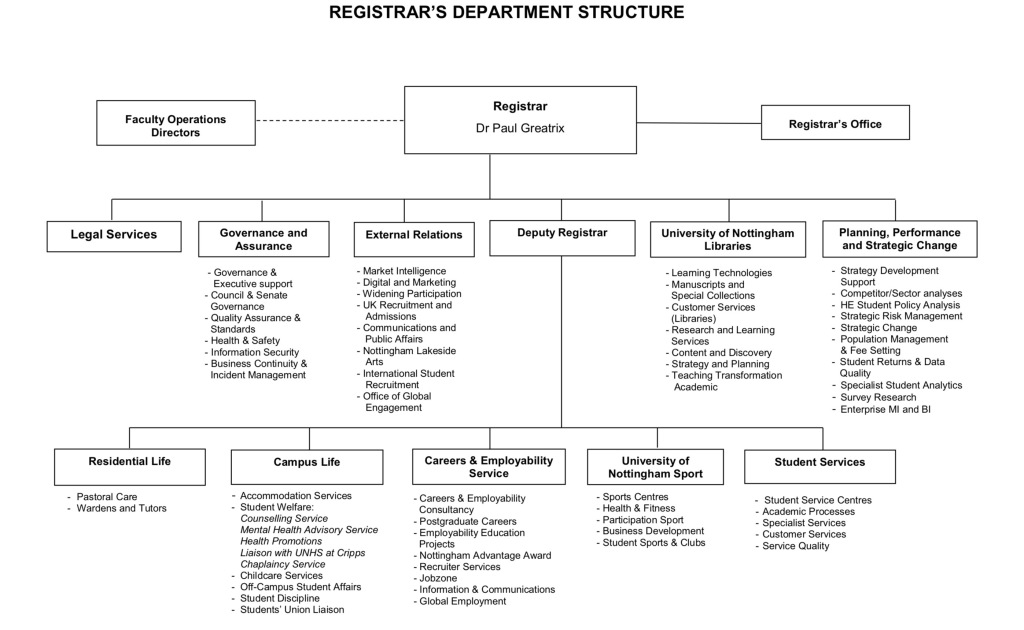

- That the £12bn test, track and trace highly-centralized scheme devised by the government (in a move that shifted existing resources from the public to the private sector, and responsibility and know-how from the local and regional bodies to the central government, thus causing a major delay and organizational havoc) would only be of marginal assistance to universities at the start of term. In other words, that universities would need their own testing and tracing schemes, until those of the government could replace them, if they wanted to prevent or, at least limit, any massive outbreaks. The chart below shows how the Test, Track and Trace scheme of the government was never really up to the task, namely, was unable to return test results fast enough for the relevant contacts to be traced and isolated in timely fashion. The same chart also shows that the test, track and trace system of the government was in no way at the capacity required for schools and universities to open; when these did indeed open, the system took a battering.

- That testing would have to be aimed at both symptomatic and asymptomatic individuals (youth are largely asymptomatic), be very wide and frequent, apply to both students and all types of staff, and occur particularly before the start of term:

“Model based evidence shows that preventing outbreaks requires high frequency screening of all students on campus. An epidemic modelling study found that, assuming typical behaviour of college students, universal screening using a rapid, cheap, high specificity test—even if low sensitivity—every two to three days is the optimal strategy.18

Frequent testing will not be feasible in all settings, but this strategy is in line with a recommendation from the UK’s Independent SAGE Behavioural Advisory Group, that if students in the UK have to physically attend campus, there should be ‘testing on or before arrival on campus followed up by further regular testing of students and staff.’19 Testing should also include lecturers and other campus staff (who may be older and at higher mortality risk from infection), and probably students living off-campus nearby.”

- That UK students should have also been asked “to restrict face to face activities and social interactions for the first two weeks of term” (according to the Independent SAGE).

- That without day to day careful monitoring of the social interactions on campus and in student halls, and an ability to intervene early and decisively, things could very quickly spiral into a situation that neither testing nor contact-tracing and isolation could any longer contain. That this was going to require an enhanced presence of very well-trained and experienced support staff in different roles on campus and in the halls, with very mobile campus-security teams also available as last resort.

- That face masks might constitute the only circuit breaker between students and between students and staff, if all other measures failed. Meaning, that masks would have to be considered as compulsory at all times not only indoors but also when more than two people are present together outdoors.

- That in the absence of adequate testing, contact-tracing and isolation would become key, resulting in a need to support students isolating in their rooms:

“Ensure full and generous support to students both to self-isolate and to access online learning resources, including practical needs (e.g., food, laundry), learning (e.g., IT, connectivity), and social and emotional needs (e.g., buddy systems, regular wellbeing checks, online events).” (see, advice from Independent SAGE)

- That “students may be reluctant to get tested if it means they and their friends must isolate for 14 days.” That “there may be further reluctance for contacts to isolate -especially if they are repeatedly contacted for different cases.” (advice from the Independent SAGE) This point deserves more attention because it might describe a reality currently underway:

“Some university students are struggling with weeks or potentially months of rolling self-isolation, because of the make-up of households in residential halls, NUS Scotland has warned. The head of the students’ union, Matt Crilly, has written to the Scottish government’s education secretary John Swinney, urging him to consider alternative, or additional, measures to self-isolation – including asymptomatic testing – to avoid long-term self-isolation among the student population. Large numbers of students are currently living in halls, in ‘households’ defined as sharing a bathroom or kitchen. When one student tests positive, all their household contacts must self-isolate for 14 days, but for asymptomatic students the clock resets every time a new member of the household develops symptoms.” (Source: Libby Brooks/The Guardian)

As any aspect related to the pandemic, this problem creates others:

“The government argues colleges and universities must continue in-person activities during lockdown so that learning isn’t disrupted. But learning is disrupted when the mode of delivery constantly changes due to staff and students yo-yoing in and out of self isolation.” (UCU)

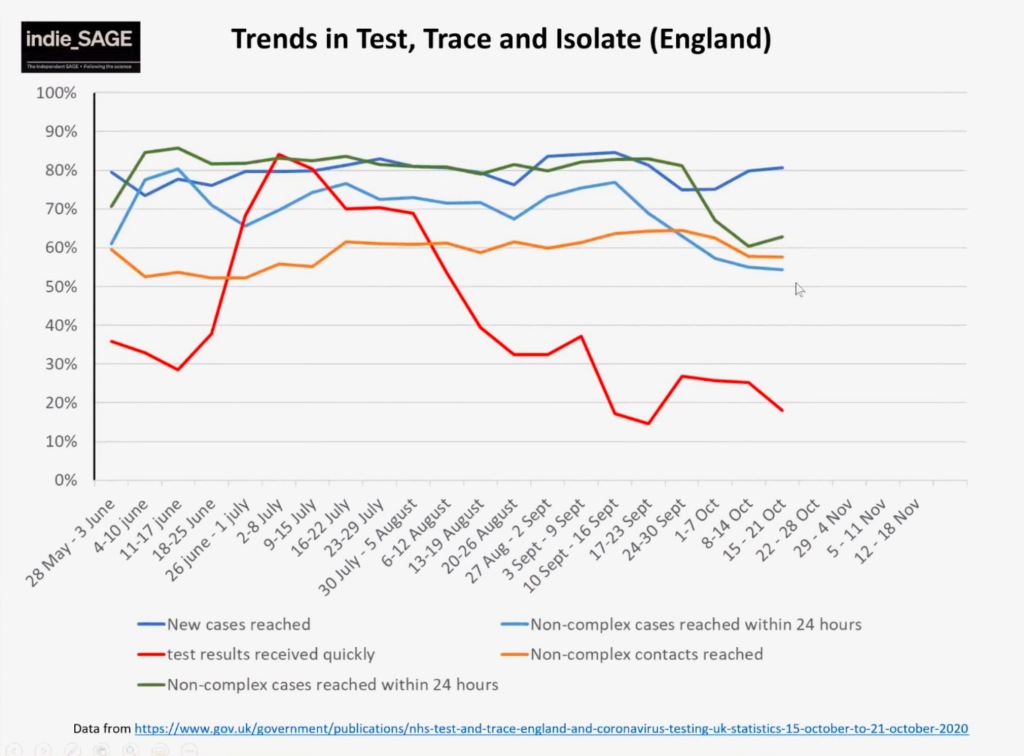

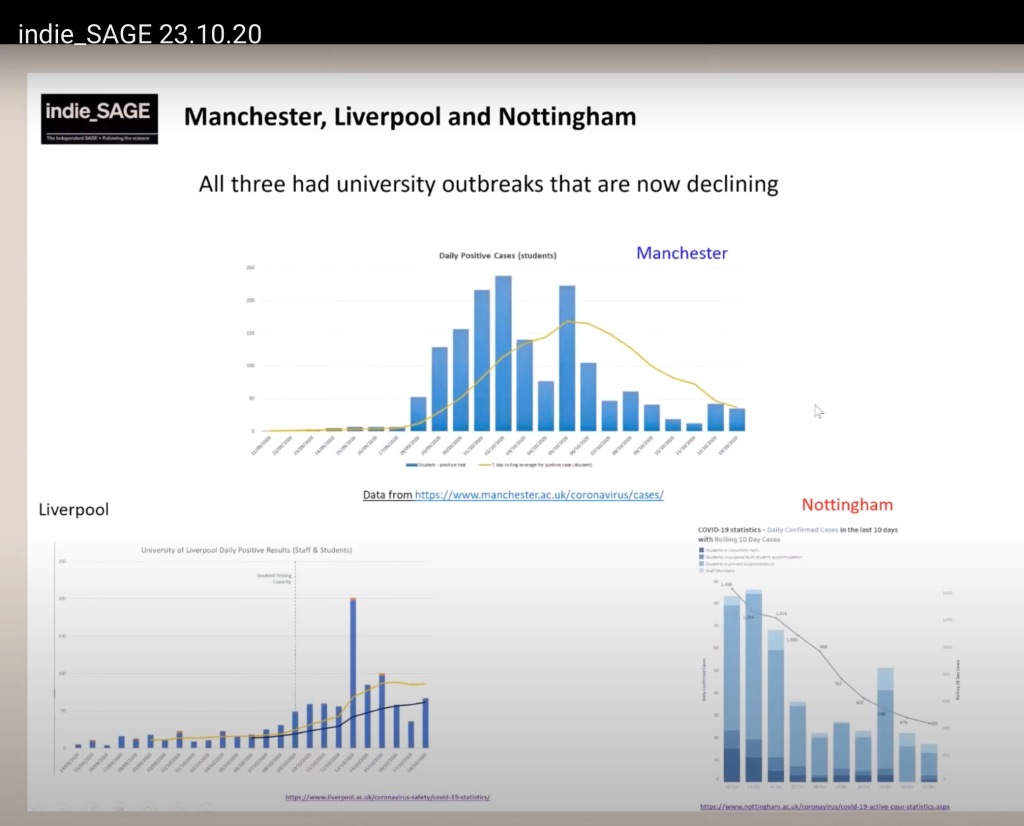

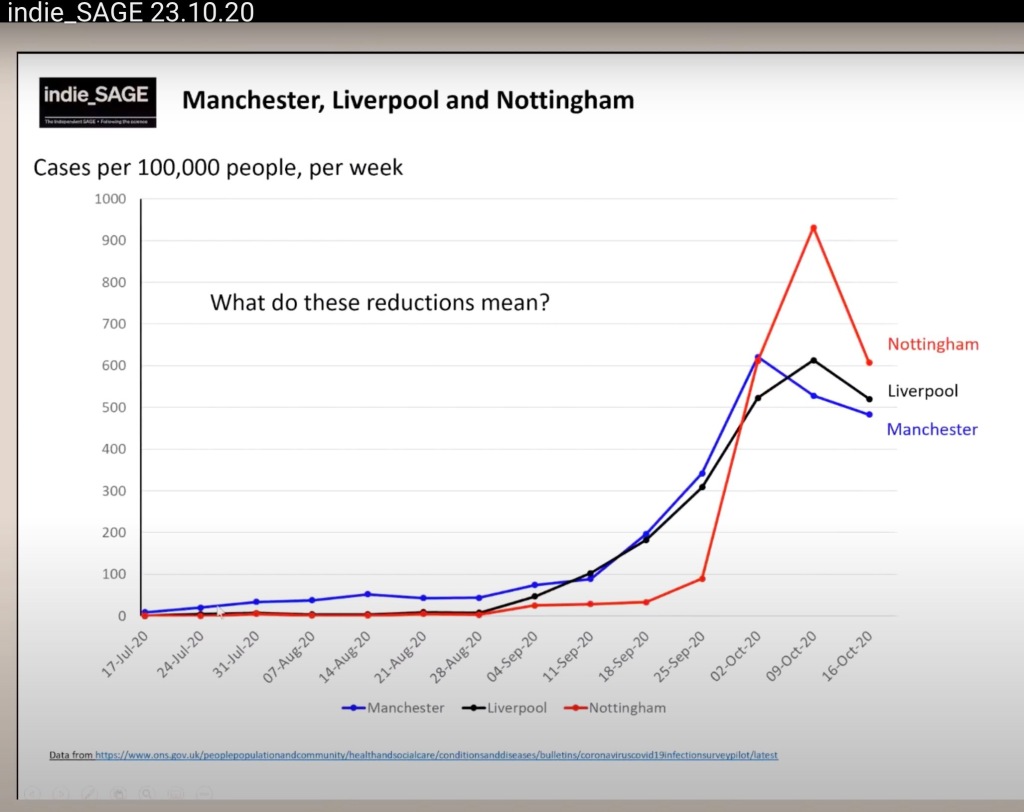

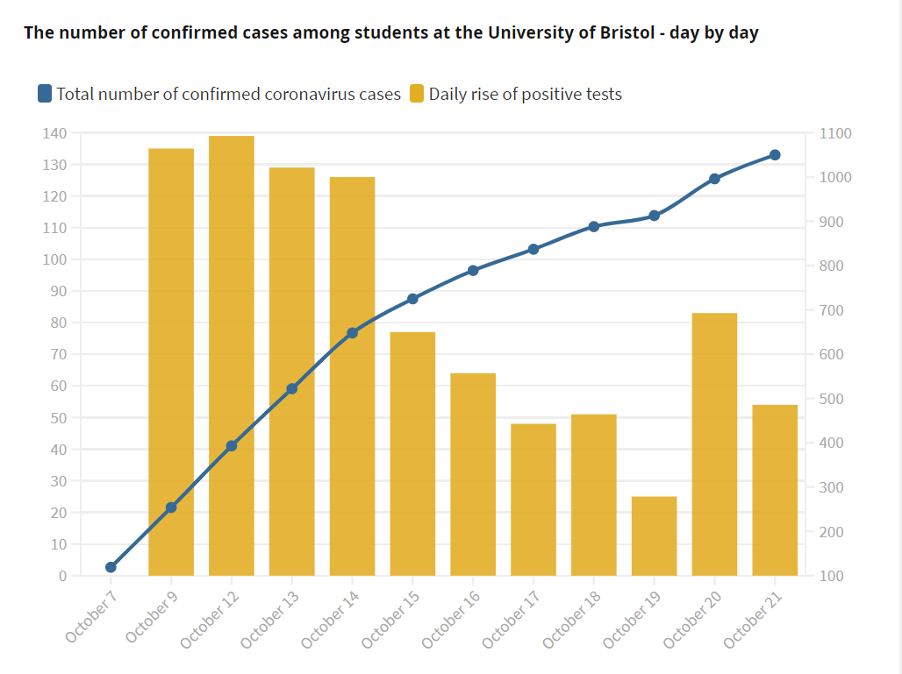

Most recently, we have been told that in those universities that had the biggest outbreaks at the beginning of October numbers are now decreasing:

But what do these reductions mean exactly?

After all, both the university numbers of daily positive cases (students) and the number of cases the ONS would have gotten from the NHS test and trace are to some considerable degree self-reported.

In the university case, they are self-reported because they are either the positive cases the university has reported as having tested (with its in-house testing) or the numbers the students have reported to the university halls after testing positive via the NHS. Currently, universities do not even seem to offer a clear breakdown of these two sets of numbers. Universities also do not currently indicate how many in-house tests they are doing per day and what proportion of those are positive cases. Moreover, while some universities offer students and staff the opportunity to book in-house testing (usually asymptomatic testing), most others do not have enough capacity to do that. That means that in the latter case, in-house testing is only used in an exploratory manner at best.

On the other hand, in the NHS test and trace case, only those students that have symptoms and want to report them can book a test:

“You can only get a free NHS test if at least one of the following applies:

- you have a high temperature

- you have a new, continuous cough

- you’ve lost your sense of taste or smell or it’s changed”

To this, we also have to add the huge delay in the return of NHS tests (see third chart up), which most certainly skews the figures.

In other words, the picture is a lot more complex than the usual announcements on social media make it sound.

It might well be the case that the virus has already spread into those areas or contexts that were much more open and conducive to transmission, and that, from now on, transmission will continue at a slower pace. It might also be the case that having seen their friends experience the harsh reality of isolation, some of the students might have decided to delete the NHS app from their phone and to stop reporting symptoms to either the NHS or the university, while generally letting only their close circle of friends know of their situation. Take for example, a simple aspect of the reality of isolation in catered student halls, where the bathroom and kitchen might need to be shared with 4-16 other students:

“In her flat, Amanda’s daughter shares a bathroom and a kitchen with four others, which makes self-isolating difficult.

Amanda said: ‘She has to get into PPE to go for a pee. Then she has to disinfect everything – the flusher, the taps, the sink, the door handle before she can go back to her tiny room. It’s the last thing you want to do when you are feeling rubbish.’

‘She can’t access the kitchen at the same time as any of the others so she goes in there alone to cook in PPE and again has to disinfect everything – the taps, the surfaces, the cooker, knives if she has used them.’

‘She ran out of fresh fruit and veg early and is now on to the stock of dried food we sent her to Glasgow with.’” (Source: here)

While the scenario described above might sound speculative, that is exactly what would happen if students felt the university is failing in supporting them fully and generously with their period of isolation (or exploiting them as a captive market for financial gain). The fact that statements of this kind kept resurfacing in the press plus the rise in “student rent strikes” (Glasgow, Cambridge, Bristol) indicate that this scenario is not at all implausible (in fact, it would suggest that anthropological research into this area is greatly needed now if we are to understand the reality on the ground):

“Since the hall is normally catered, food during lockdown is delivered in bags to rooms.

She said: ‘But sometimes the meals are hours late or don’t arrive at all.’

‘Vegetarians have been delivered chicken meals – and when students call to complain, the numbers go straight to voicemail.’

‘Students in blocks which aren’t yet locked down have been passing food through windows to friends who have been told to isolate.’

She said communal areas are out of bounds even to groups of less than six and anyone stepping outside their room is ‘shouted at’ by security.

‘It’s like a prison or the end of the world. People can’t exercise, there is no-one around on campus, it’s really weird,’ the student continued.

‘We wouldn’t even mind the isolation if only we had an email explaining it.’

‘I’ve seen a good few people’s parents turning up to fetch them, telling them, We don’t care about the fine – get in the car.’” (Source: here)

“Despite registering as self-isolating on the first day it took just over a week for the food parcel from the university to arrive, and then, when it did, it was only suitable for two people and we were a flat of six,” he said.

Not only were the food packages insufficient, students said, but in many cases they did not contain essential items like cleaning products, tampons and sanitary towels.” (Source: here)

“At Lancaster University, an opt-in deal lets students get three prepared meals — including a cold breakfast, cold lunch and an evening meal which is to be heated — delivered for £17.95 per day. The deal is supposed to be a potential option for students who are self-isolating due to the coronavirus pandemic. However, a petition shared by students has accused the university of “profiting” off students in self-isolation, claiming the ingredients per portion cost less than £3.

‘These parcels … are the only practical way for many to get supplies, given a shortage of delivery slots,’ the petition, started by Kyle Westrip on Change.org, says.” (Source: here)

The problem with this scenario, of course, is that if students who have symptoms are not self-isolating, then university staff (cleaning staff, catering, porters, security) and teaching staff who engage face-to-face with students are placed, unbeknownst to them, at considerable risk. Some HEIs seem well aware of this, which is likely why Universities such as the University of Manchester are asking students “to report any staff or students who have had a positive Covid-19 test or are isolating/quarantining but have no positive test.”

- That the risk-areas in universities were “first-year halls of residence and face-to-face teaching.” This had been identified in SAGE modelling, which means, the government and PHE would have known this ahead of time:

“Prof Mark Woolhouse, who sits on the government’s pandemic modelling group SPI-M, said the situation was ‘entirely predictable’ and had been modelled. He said students were not to blame for the outbreaks and with students converging from around the country it was ‘inevitable there would be some spread’. Modelling showed the risk areas were first-year halls of residence and face-to-face teaching, he said. [my emphasis]”

While “face-to-face teaching” has been widely identified as high-risk much before the start of term (with no avail until huge outbreaks and subsequent industrial action), Professor’s Woolhouse’s statement from the 27th of September should also not have come as a surprise, considering the fact that catering halls (which, generally, are first-year halls of residence) are more like Covid-19 tinder-boxes than any other type of halls, both because of their internal layout (many students sharing a bathroom and kitchen) and because of how closely they are located to each other on any campus (meaning thousands of students can be in close interaction with each-other). Surely, those special committees tasked with assessing all university buildings for their level of risk in terms of Covid-19 would not have missed such a glaring fact.

- That without adequate induction so that the freshers/students are “meaningfully engaged in the reopening planning process,” understand the threat of the virus to themselves and the wider community, and are encouraged to study and monitor the disease as a public health crisis throughout their life on campus and in the city, these new arrivals would continue to dismiss warnings about the virus (as their age-peers and, sometimes, parents, have generally been doing in the months before, due to our divided politics and the highly politicized understanding of the virus in the US-UK media), and seek to live that student life that every generation of students starting university feels entitled to celebrate, and for which British universities are famous during Freshers’ Week. For those unfamiliar with the term, ‘Freshers’ Week’ has been aptly described by the New York Times as “Britain’s debaucherous baptism into university life, complete with trips to crowded pubs and dorm room parties” and the name does not do it justice because it can last even 2 or 3 weeks (like it did this start of term). I emphasize the importance of this term here because this social phenomenon, a very important part of the organizational and marketing side of the UK university, is absolutely key to understanding the huge Covid-19 university outbreaks at the start of term. We should not assume, however, that parties during Covid-19 tier lockdowns are only a student phenomenon.

- That “essential in-person teaching and learning (e.g., components of laboratory or practice-based courses)” should be made “contingent on the regular testing of students and staff, with a ‘dashboard’ approach as adopted by US Colleges.” I cannot emphasize it here how important this particular dashboard approach is, one that I do not believe any UK university has replicated yet: https://news.northeastern.edu/coronavirus/reopening/testing-dashboard/

It must be remembered here that universities were not generally the first to reveal the news about their positive cases of Covid-19. PHE directors, as has been discussed before, have also been reluctant. Universities and PHE directors generally started to report on the numbers to a limited extent, only after articles about the struggles of students with isolation in the halls appeared repeatedly in the press. The Covid-19 reporting of the Universities generally came in response to such articles and to the resultant stir in public opinion and also as a manner of tackling the huge number of parents desperately calling in for information. When the reporting did arrive, it generally failed to mention the numbers of students isolating. This could have been an important piece of information for members of the academic or administrative staff (including cleaners, catering etc.) universities were trying, quite forcefully in some cases, to invite back on campus. It is one thing to say you have 110 positive cases on campus. It is quite another to say 127 students tested positive for Covid-19 and “about 1,700 university students have been told to self-isolate” (Manchester Metropolitan University) or that 114 have tested positive and around 1,000 students are self-isolating. The Guardian states that “After examining all the published figures of Covid-19 cases at universities, UCU found Newcastle, Nottingham, Manchester and Northumbria universities have all reported having more than 1,500 cases of Covid on campus since the start of term.” Have any of these universities indicated how many students had been in self-isolation in the weeks where cases had been at peak level? Thousands most likely, but how many thousands? The standard response, has more often than not been to avoid the issue of the numbers of students in self-isolation through management speak:

“A spokesperson for the university said: ‘As of Friday October 2, we can confirm that we are aware of 770 Northumbria University students who have tested positive for Covid-19, of whom 78 are symptomatic.’

‘These students are all now self-isolating. Their flatmates and any close contacts are also self-isolating for 14 days in line with government guidance and have been advised to contact NHS119 to book a test as soon as possible should symptoms appear.’”